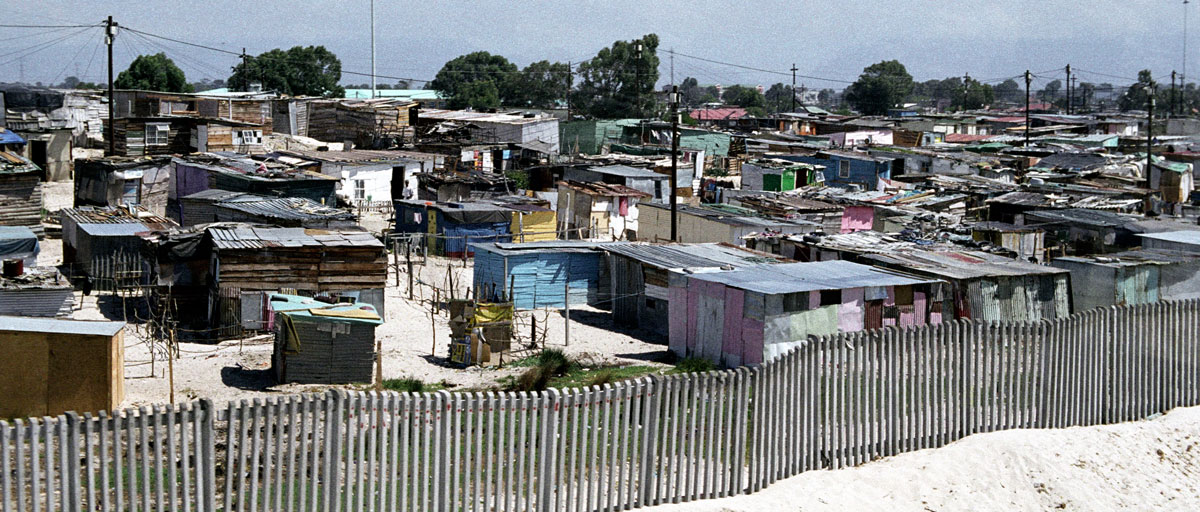

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Urban Environmental Injustice

Privileged people, privileged plants

A study of Cape Town’s plant life shows how post-apartheid poverty and inequality is mirrored in and exacerbated by ecological patterns

- In Cape Town ecological character and qualities follow racial lines and patterns of wealth. This is maintained by the inequity of apartheid planning.

- In neighbourhoods of lower socio-economic status there are fewer green spaces and decreased resilience to environmental shocks.

- The study showed decreasing plant diversity as landscapes become increasingly urbanized and the authors call for more ecologically minded planting in public green spaces.

From 1948 until the early 1990s, the practice of institutionalised racism, known as apartheid, was in place in Cape Town and across South Africa.

The ghost of apartheid lives on not only as developmental, educational and wealth disparities, but also in the ecologies of the city.

A study published in Landscape and Urban Planning highlights the connection between the racial composition and wealth of a neighbourhood and its level of ecological poverty.

Centre researchers Erik Andersson, Julie Goodness and Thomas Enqvist were part of a team of researchers conducting in-depth ecological surveys that measured functional traits of plants, which give an indication of resilience and vulnerability to environmental shocks.

In this paper we make a further contribution from the global south towards understanding the ecology of cities. We analyse how urban management impacts plant species richness and key plant functional traits.

Pippin Anderson, lead author

Urban ecologies and urban filters

Cape Town is a biodiversity hotspot. It is situated in the smallest most diverse floristic region in the world, the Cape Floristic Region, which holds 44% of the flora of South Africa. Despite its beauty and cultural diversity, racial fault lines run deep and poverty levels are high.

When a landscape is urbanized there is a filtering of the ecology whereby some species thrive, and others are suppressed, or weeded out. This human mediated filtering process can be by design, as in gardens. Filtering can also happen as a by-product of human processes like fire suppression and pollution, which change the assemblages of plant species.

In the study, the researchers consider how different filtering processes have led to impoverished ecologies in Cape Town.

With humans in control, there has been a shift away from plants that need animals to spread their seeds and for pollination.

Co-author Erik Andersson argues, “The ability to purchase plants from nurseries renders the need to produce and disperse seed obsolete.” These unnatural ecologies are especially vulnerable, which pose a problem - as global populations grow, so too will the importance of our green spaces.

“For the majority of the next generation, the green spaces of our cities will be the first ‘natural’ landscapes they encounter in life.”

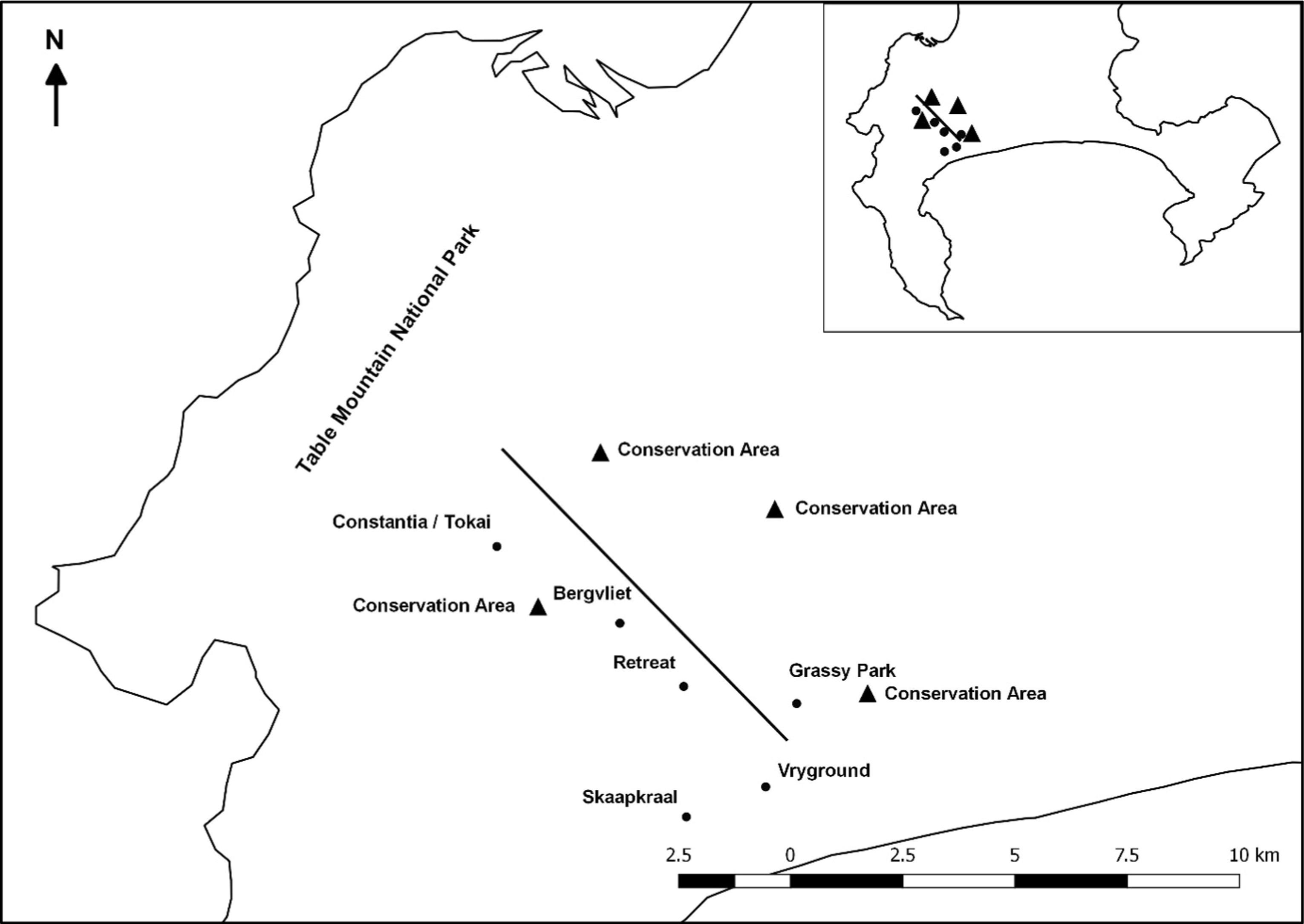

Map of the study site showing the neighbourhoods and conservation areas sampled across the socio-economic gradient within the City of Cape Town. Click on illustration to access scientific study.

Apartheid planning resistant to change

Environmental injustice is often exacerbated by systematic traps, making it difficult to depart from injustices from the past. The researchers found that plant communities mirror historical apartheid planning that is resistant to change.

Through apartheid planning in Cape Town different racial groups were provided designated areas in which to reside.

Julie Goodness explains, “privileged white people were allocated neighbourhoods that received excellent municipal services and had easy access to the city centre while black and coloured people were forcefully relegated to further flung neighbourhoods with limited municipal infrastructure and services."

And today, the current market-based allocation of housing has done little to transform racially and socio-economically distinct neighbourhoods.

The luxury effect

The authors combined an environmental justice approach with a thorough ecological survey method. They did not simply measure plant cover and biodiversity, in their study they also calculate ecological functionality.

Plots were surveyed across an urban to natural gradient and along a socio-economic gradient. At one end of this gradient, are the privileged white neighbourhoods, and at the other end are poor, predominantly black neighbourhoods. The observed decline in species richness along this gradient is known as the luxury effect.

In poorer black neighbourhoods, there are fewer green spaces, and less diverse plant functional groups. This means that ecological functions are less resilient to environmental shocks.

For example, some plants are important in urban settings for temperature regulation, and if there are very few species providing this service, then the neighbourhood becomes more vulnerable to heat if these plants are wiped out in a drought or other environmental shock. When more species perform the same functions, as was found in wealthier white neighbourhoods, the service of for example temperature regulation is more likely to withstand shocks and changes.

Through this lens of environmental injustice, environmental drivers that perpetuate social inequality were made clearly visible.

The authors conclude with explicit recommendations, including the creation of a database of locally appropriate indigenous species with associated traits and horticultural requirements as a useful next step.

“This could be used to inform city planting schemes as well as public campaigns run through nurseries, with greater attention required in poorer neighbourhoods.”

Methodology

The researchers made comparisons along a gradient of natural to urban landscapes, and also along a socio-economic gradient - from wealthy predominantly white neighbourhoods to poor predominantly black neighbourhoods. Pre-apartheid all neighbourhoods had the “Cape Flats Sand Fynbos” vegetation type.

Sampling was conducted across 156 plots across the two gradients. They measured plant cover and diversity as well as plant functional traits such as growth form, rooting depth, pollination mechanism and seed dispersal mechanism. These presented opportunities to consider both human management and ecological aspects. From these, they made trait profiles of the different plant communities.

Statistical analysis was carried out to detect correlations. They also controlled for soil fertility, since wealthier communities could have been built on more fertile soils.

Anderson, P., Charles-Dominique, T., Ernstson, H., Andersson, E., Goodness, J., Elmqvist, T. 2019. Post-apartheid ecologies in the City of Cape Town: An examination of plant functional traits in relation to urban gradients. Landscape and Urban Planning Volume 193, January 2020, 103662

Erik Andersson studies flows of multiple ecosystem services and benefits, often with cities and urban residents as the final end users, the impact this use has on both ends of the supply chain, and how and when these flows may change over time.