A new article published in the Journal of BioScience offers a novel way to understand how and why ES benefits are unequally distributed across cities and their inhabitants. Photo: A. Maslennikov/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Access to ecosystem services

Life is often greener on the other side of the fence

Access to green spaces in cities is a class issue. How can ecosystem services be distributed more equally?

- Amid urban growth, making sure people living in cities have access to public services including ecosystem services remains a challenge

- The study explores how gardens, woodlands, ponds, water courses in cities can fit in a socially inclusive way in areas otherwise dominated by concrete buildings and roads

- In order to design resilient cities, the authors recommend city planners to work through three analytical filters to make cities more liveable

If you live in a city and have easy access to green areas and ecosystem services you should count yourself lucky and privileged. Cities today host more than half of the world’s human population and this figure is set to increase if current rural-urban migration trends remain. Making sure that all these people have access to public services including ecosystem services (ES) remains a challenge, and one the that goes well beyond whether or not there are green spaces in the city or not.

Managing the infrastructure - mixing green, blue and grey

A new article lead-authored by centre researcher Erik Andersson and published in the Journal of BioScience offers a novel way to understand how and why ES benefits are unequally distributed across cities and their inhabitants. Andersson collaborated with researchers from multiple cities and institutions for the study that is part of a larger project called ENABLE - Enabling Green & Blue Infrastructure Potential in Complex Social-Ecological Regions. Under ENABLE, researchers are working across six cities in Europe and North America to leverage the “potential of green and blue infrastructure (GBI) interventions” while taking in the perceptions of city dwellers in a more socially and environmentally inclusive way.

Green and blue infrastructures refer to spaces such as gardens, woodlands, ponds, water courses in cities that are otherwise dominated by grey infrastructure i.e. concrete buildings and roads. These green spaces provide vital ecosystem services to city residents such as temperature regulation and pollution control while also creating spaces for recreation and social activity.

It is vital then to analyse the complementarity and interdependencies of green, grey and blue infrastructural systems in cities as the extended infrastructure supporting and directing the flow of ecosystem services benefits.

Erik Andersson, lead author

Not all city residents, however, can easily access these spaces or the ES they offer. In fact, recognising green, blue and grey infrastructures as interconnected social-ecological entities can help make sure that different groups and different interests have equitable access to ES benefits, and infrastructure design can either help or hinder the flow of benefits. For example, in a city with unreliable public transportation those living closer to wooded areas have an unfair advantage as compared to those living further away.

Andersson, project coordinator for ENABLE, explains that “the ENABLE approach aims to advance the knowledge of how to work broadly with the functionality of GBI more effectively and equitably – that is, how to negotiate trade-off to ensure the delivery of benefits across diverse groups.”

Tomorrow’s resilient cities

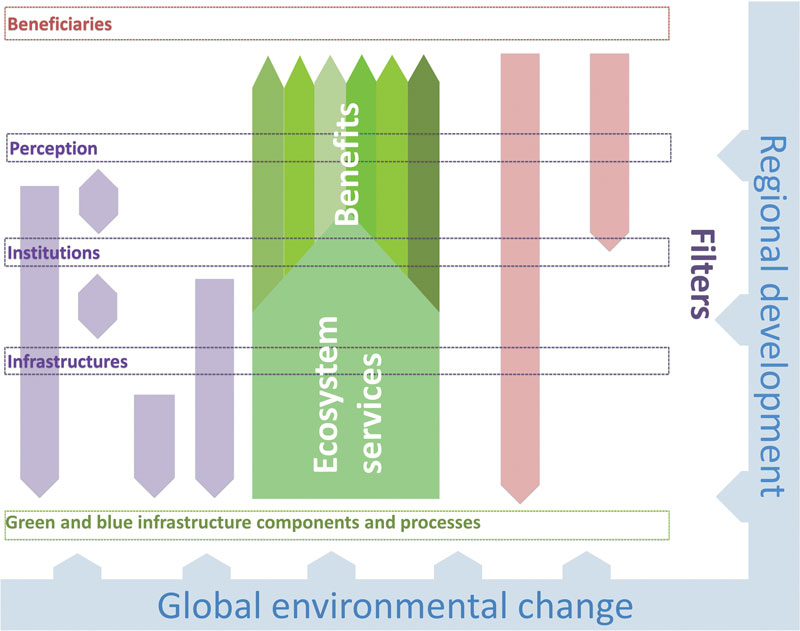

In the article, Andersson and his colleagues discuss how three systemic factors or filters, affect the flow of services: the three factors being the interactions among green, blue and built (grey) infrastructures, the regulatory power and governance of institutions, and people’s individual and shared perceptions and values. The article also offers a dual framework for assessing the performance of alleged nature-based solutions.

Filter 1: Interconnectedness between GBI and urban infrastructures

Infrastructures is the functional backbone of any city region. They provide mobility, connectivity and decide the overall availability of different resources and services.

Andersson explains: “It is vital then to analyse the complementarity and interdependencies of green, grey and blue infrastructural systems in cities as the extended infrastructure supporting and directing the flow of ES benefits.”If located strategically and connected to the city, green and blue spaces can contribute to novel solutions to sustainability challenges and contribute to urban resilience.

Filter 2: Institutional factors

The authors highlight the importance of institutions in influencing how individuals and groups pursue different opportunities and what benefits are viable for them to access. They define institutions as “the formal and informal rules of a governance system that are situated within a particular social, economic and political context.”

As an example, it is common in cities to find large private gardens whose use is restricted to certain wealthier community members. Such conditions exacerbate environmental inequities in cities where ES may already be limited. Policy planners can address such issues, but this would necessitate institutional arrangements wherein voices of a diverse set of stakeholders (e.g. from across different socio-economic strata) are incorporated into urban planning.

Filter 3: Individual values and perceptions

Even when there are no formal restrictions to accessibility, differences in knowledge, education, available information, and individual circumstances may privilege some voices and interests more than others.

“These differences in opportunities to realize individual interests remain underdeveloped in ES research and practice,” Andersson explains.

The paper emphasizes the need for in-depth study of how individuals’ perceptions and values influence the access to GBI – various factors such as age, education levels, ethnicity and socio-economic circumstances may enhance or limit accessibility. Andersson further emphasises that “methods chosen for assessing the experiential quality of the urban landscape need to be sensitive to the nature of the benefit, conditions under which it is available and the interpersonal differences among beneficiaries”.

The systems model. The green and blue infrastructure componentsand their different ecological qualities provide the first necessary preconditionfor ecosystem services. Systemic factors (the purple boxes) can enable or disablethe flow of ecosystem services and thus influence translation of ecosystemservices into various benefits to beneficiaries (the red box). Downward orientedarrows represent the feedback from beneficiaries and other actors (the redarrows) and different filters (the two-way purple arrows) that can influenceeither other filters or the green and blue infrastructure components thatunderlie ecosystem service supply.

A major feat

In light of climate change, increasing population pressures and shrinking green spaces improving access to ES benefits in cities is going to be ever more challenging. In order to design resilient cities, the authors recommend city planners to work through these three analytical filters to not only make cities more liveable today but also to prepare for the future. However, resilience may not necessarily mean equitable, and the justice lens is a much needed counterweight to resilience building.

“With billions already calling cities their home, getting urban planning right would be a major feat,” Andersson concludes.

Anderson, E., Langemeyer, J., Borgström, S., McPhearson, T., et.al. 2019. Enabling green and blue infrastructure to improvecontributions to human well-being and equity in urban systems. BioScience, , biz058, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz058

Erik Andersson is an associate professor who is researching multifunctional landscapes, and leading projects on green infrastructure and how to improve them.

Timon McPhearson is an associate research fellow focused on urban resilience and the role of ecosystems as nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation in cities.