A new study presents database on more than 40 years of fishery conflicts, with trends across time and geography examined. The study also offers insights on conflict responses and critical research gaps. Photo: U.S. Coast Guard

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

FISHERIES CONFLICTS

Forty years of conflicts

New study presents and analyzes first longitudinal database on fisheries conflict

- New study created new database on fisheries conflict, the International Fishery Conflict Database with conflict cases from 1974-2016

- Examines past trends over time and between countries

- Study highlights past responses that have helped mitigate conflict, and critical research gaps

Sometimes looking back can help us move forward. Learning from past mistakes, successes, and everything in between can help show what should be done in the future. Case studies across all disciplines do this. Looking to the past for a deeper understanding of fisheries conflict is no exception.

A new article, published in Global Environmental Change, looks back at more than 40 years of fisheries conflict. The authors, centre researchers Jessica Spijkers, Robert Blasiak, and Henrik Österblom, and colleauges Gerlad Singh and Philippe Le Billon form University of British Columbia, as well as Tiffany Morisson from James Cook University, have created the International Fisheries Conflict Databased (IFCD) using past media reports form the years 1974 to 2016. They then used descriptive statistics to examine what types conflicts happened and how they occurred.

In the face of climate change impacts, resource scarcity, illegal activity and territorial disputes, conflict management across political borders becomes essential for environmental sustainability, human health, and maritime security.

Jessica Spijkers, lead author

Trends across four decades

By looking at past fisheries’ conflicts, the authors were able to highlight a number of trends.

First, the authors found that conflict has increased over time, with the USA being involved in the most conflict, followed by Canada, Japan, China, and the EU. Furthermore, the authors found that of these high-conflict countries, disputes tended to be within the same continent.

Spijkers also points out, “Our analysis suggests that the nature of, and countries engaged in, fisheries conflict have changed substantially over the past 40 years. Many of the countries most frequently involved in conflict are large industrial fishing powers known to dominate global fishing efforts, but they have engaged in conflict at different points in time.”

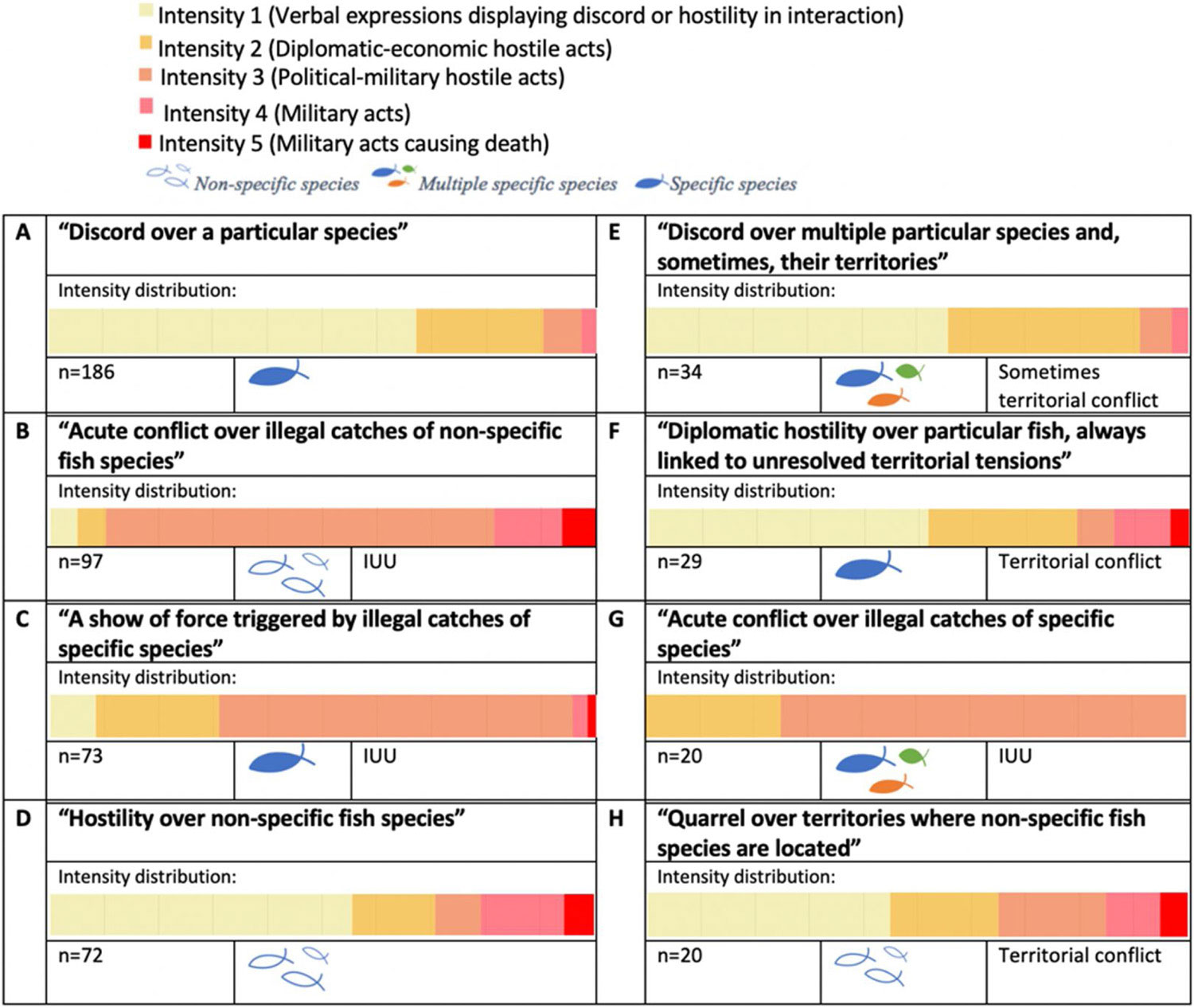

The authors’ statistical analysis also grouped conflicts into eight different types:

Type A – Discord over a particular species

Type B – Acute conflict over illegal catches of a non-specific species

Type C – A show of force triggered by illegal catches of specific species

Type D – Hostility over non-specific fish species

Type E – Discord over multiple particular species and, sometimes their territories

Type F – Diplomatic hostility over particular fish, always linked to unresolved territorial tensions

Type G – Quarrel over territories where non-specific fish species are based

From these groupings, the authors were further able to identify more trends. For instance, the most common time of conflict were over a particular species. Conflicts that involved more than two countries were rare, but if there were more than two countries involved, it tended also to be over a specific species.

The authors were able to point out that deadly conflicts occurred less over non-specific species, and instead were over catches or territory.

Three frequent regional conflicts

The database revealed that three different constellations of conflict were particularly frequent: intra-North America conflict and intra-Europe conflict, conflict between Europe and North America, and intra-Asia conflict. “Collectively they represent 74.8% of all conflict events,” Österblom explains.

Conflicts within North America or within Europe make up 19.2% and 17.1% of all IFCD conflict events, respectively. They have also tended to be species-specific conflicts that have flared up over cod, salmon, and Albacore tuna stocks in North America in the past, and more recently in Europe over northeast Atlantic mackerel and Atlanto-Scandian herring.

Conflicts between Europe and North America, which make up 11.5% of all IFCD events, also tended to be over specific species, such as cod or American plaice, and were consistent over time. Territorial tensions (Type F) between Europe and North America over a specific fish also occurred and caused some diplomatic hostility between nations. However, conflicts between these two continents have decreased over time

Finally, intra-Asia conflicts were the most common (26.9% of all IFCD events) and most diverse. All of the eight types of fisheries’ conflicts were represented in the database, and the most violent events took place between Asian countries.

What should we do?

Besides responding swiftly to conflict once it has erupted, countries also need to manage the incremental stressors that either drive conflict to erupt in the first place, or that push fisheries conflicts to become systemic risks. For this, more region-specific research is needed into underlying and proximate drivers of conflict, and how they interact to produce wider systemic risks, Spijckers explains.

The authors also suggest a number of response strategies for mitigating conflicts. These include: a shared scientific understanding; shared enforcement activities; side payments, such as incentives for a coalition in a dispute; long-term management plans; and strict illegal, unregulated, and unreported policies, such as requiring vessel monitoring systems on all ships.

The authors also go on to highlight a number of important drivers, or aspects in fisheries conflict research: climate change, the drivers of conflict in Asia, and fish abundance as a conflict driver. Understanding what driver conflict can ultimately help mitigate tensions.

“Research on conflict drivers within fisheries can also further facilitate a discussion on indicators of potential imminent fishery conflict and how policymakers might use those to develop responses,” adds Blasiak.

Past fisheries conflicts have been successfully resolved or evaded. By looking to the past, the hope is that less damage to fish stocks and international relations will be done in the future.

Methodology

To develop the international fisheries conflict database (IFCD), the authors used the LexisNexis Academic (LNA) database, which is the world’s largest collection of media reports. The search terms they selected were aimed at pulling results that could detect the actions and behaviours that signified different levels of conflict.

The authors then examined each reported conflict, and ended up with 531 conflicts in their database from 1974 to 2016, and categorized each conflict event on an intensity scale from 0, non-significant acts, to 5, military acts causing death (see Table 1 in paper for more details). They then applied descriptive statistics to the database. They also used non-metric multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis.

They also checked to see if the IFCD was biased as a result of: English media reports or Press Freedom Index Scores: While the authors did not find any evidence for bias within their collected data, the authors note that the IFCD is likely underreporting the total amount of fisheries conflict in non-English speaking countries, as the data was collected from English media.

Spijkers, J., Singh, G., Blasiak, R., Morrison, T.H., Le Billon, P. and Österblom, H., 2019. Global patterns of fisheries conflict: Forty years of data. Global Environmental Change, 57, p.101921.

Jessica Spijkers is a PhD candidate at the centre and James Cook University's ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. Her work focuses on international relations and conflicts around fisheries.

Robert Blasiak is a researcher at the centre focusing on stewardship within the seafood industry and issues surrounding marine genetic resources.

Henrik Österblom is a professor and science director at the centre. His research explores ocean stewardship, global cooperation, and marine ecosystems.