Over the past 50 years, many initiatives have tried to address the many ecological and social challenges in the Sahel region. The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative (GGW) may have a better chance of succeeding.

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

REGREENING THE SAHEL

The right tree at the right place

Why regreening the Sahel is more than just creating a wall of trees and why one initiative may actually succeed

• Over the past 50 years, a large number of development initiatives have tried but failed to address the many ecological and social challenges in the Sahel region

• The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative may have a better chance of succeeding than previous initiatives

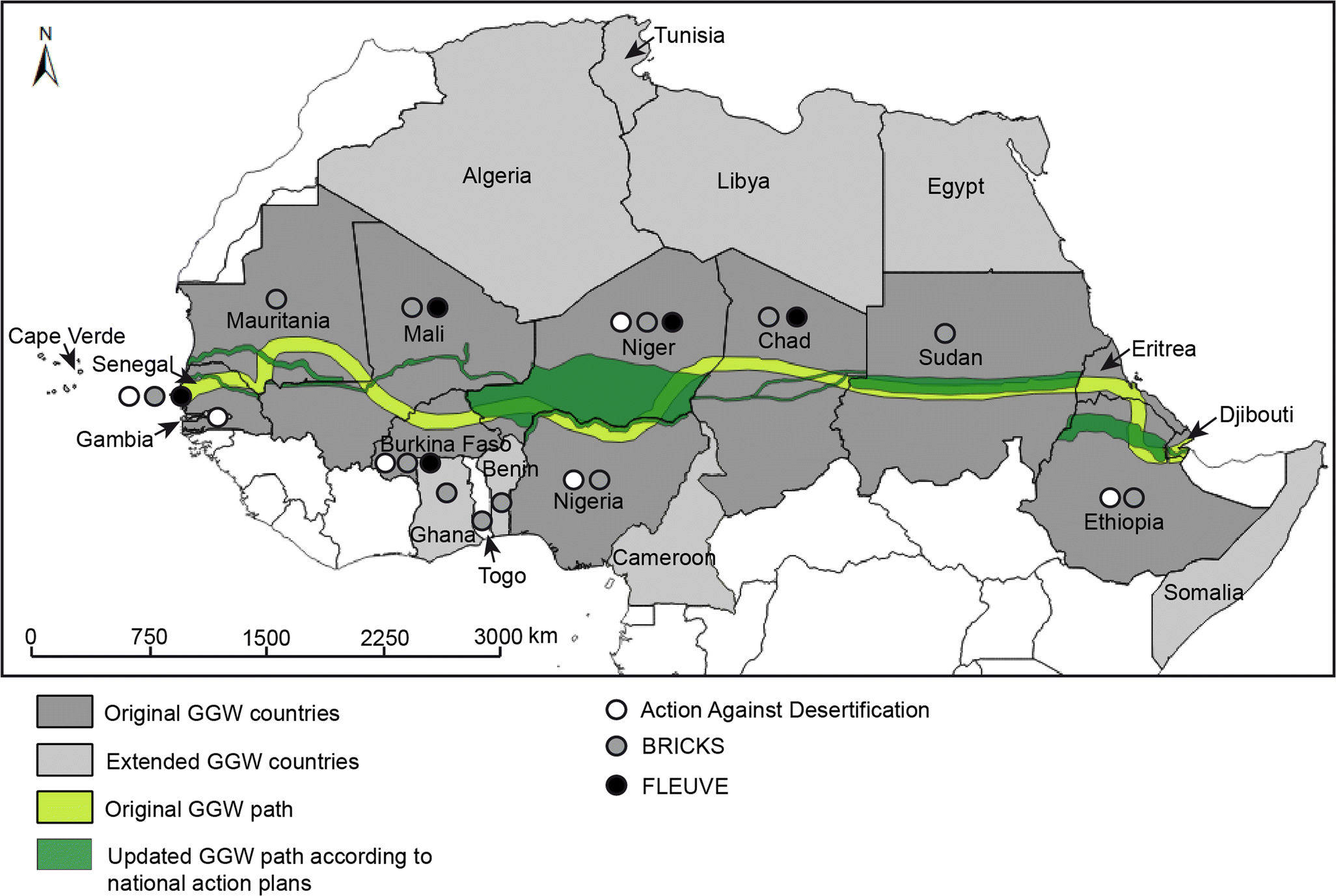

• The pan-African programme is the most ambitious development programmes to date with a total of 21 African countries involved

The Balanites aegyptiaca tree is a tough nut to crack. Even under the most arid conditions that is Sahel, the biogeographic zone of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian Savanna to the south, the tree manages to produce a wide range of useful ecosystem services such as food and medicine. In the same region, other tree species barely survive. It also illuminates the importance of knowing what species are resilient enough to generate long-term benefits. Sahel is commonly described as a poverty trap and a hotspot for effects of global climate change.

Over the past 50 years, a large number of development initiatives have tried to address the many ecological and social challenges in the region, but only with a limited degree of success. Increasingly over the past decade, resilience thinking has been applied as a way to address what has been acknowledged to be a complex challenge. Just planting a long corridor of trees will not solve anything.

The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative could be a potential catalyst in promoting collaboration between countries in the Sahel. A collaborative fight against a larger scale “common enemy” like climate change could generate stronger solidarity among member states.

Deborah Goffner, lead author

Consolidating different people with different knowledge

In an article recently published in Regional Environmental Change, centre researchers Deborah Goffner, Hanna Sinare and Line Gordon offer an analysis of the Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative (GGW) and why it may have a better chance of succeeding than previous initiatives. The pan-African programme is the most ambitious development programmes to date with a total of 21 African countries involved.

But changes will take time.

To succeed, the authors write, it must “intelligently gather and centralise pre-existing interdisciplinary knowledge, generate new knowledge, and integrate knowledge systems to appropriately navigate future uncertainties.” That may sound like a nice piece of science jargon, but it nevertheless encapsulates the essence of what is needed to succeed in the Sahel: different people need to talk to each other because they all come with different expertise that is important for a variety of social and ecological contexts.

The resilience framework is central to this because it departs from the acknowledgement that humans and nature interact and are dependent on each other.

Mosaics, not walls

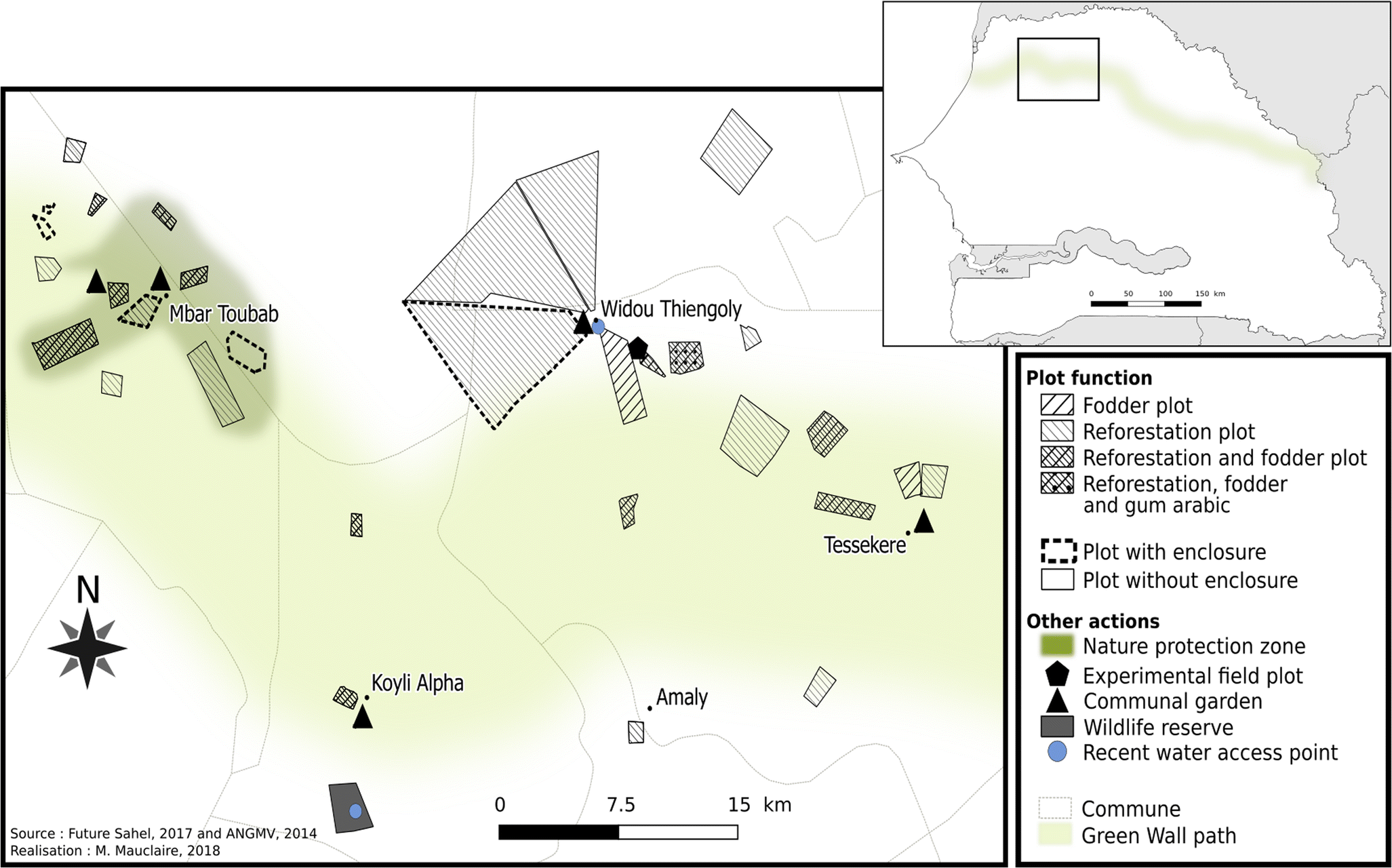

Although the name of the programme indicates the mission to create a “wall of trees”, GGW focuses more on designing landscape “mosaics”, where any action is scaled to the level it is supposed to serve. This change of focus has improved the changes of GGW to be successful, the authors argue.

Through consultation with local stakeholders, the locations of reforestation plots of variable shape, size, and function are decided and erected throughout the landscape. Says lead author Deborah Goffner: “Sahelian populations rely heavily on ecosystem services such as food, energy, medicine, construction materials and livestock feed for their daily needs. The GGW aims to improve production and access to these services.”

To do this, knowledge of the fine-grained diversity of how people use the landscape units, as well as broader pattern that it creates in the landscapes as a whole, is necessary.

“We underline the importance of combining scientific knowledge and the knowledge and experience of local Sahelian populations to find the best solutions through participatory approaches,” Goffner says.

An example of a mosaic landscape created by GGW actions in Northern Senegal. Click on illustration to access scientific study

Large-scale benefits are possible

According to the authors, the GGW is a unique opportunity for creating resilient Sahelian landscapes. Its continental geographic scope means that large-scale benefits are possible. But there are hurdles on the way. One is time: the GGW must juggle operating at different paces. There is pressure to see rapid positive outcomes, such as meeting the Bonn challenge target to restore 350 million hectares worldwide by 2030. Yet ecological restoration to preserve and rejuvenate natural resources like trees and water often takes decades. Further sensitivity to power relations, suitability of particular actions and continuously improved implementation will be needed.

Still, the GGW has every opportunity to succeed, Goffner and her colleagues conclude:

“The GGW could be a potential catalyst in promoting collaboration between countries in the Sahel. A collaborative fight against a larger scale “common enemy” like climate change could generate stronger solidarity among member states.”

Goffner, D., Sinare, H. & Gordon, L.J. 2019. The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative as an opportunity to enhance resilience in Sahelian landscapes and livelihoods. Reg Environ Change, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01481-z

Deborah Goffner is a visiting senior scientist working in the Senegalese Sahel at the research-development interface in the context of the Great Green Wall for the Sahara and Sahel Initiative.

Hanna Sinare’s research focuses on the multifunctionality of landscapes dominated by smallholder agriculture, and on what can attract new generations to produce food sustainably in these landscapes

Line Gordon is the director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre. She conducts innovative research that combines work with small scale farmers in Africa, global models of land-use and rainfall interactions, and culinary innovators.