New research demonstrates how wellbeing benefits derived from ecosystem services in tropical coastal communities are unequally distributed between men and women. Photo: O. Henriksson/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Ecosystem services and gender

Ecosystem services for men, ecosystem services for women

There can be stark differences in how men and women use and experience ecosystem services. That has significant impact on their well-being

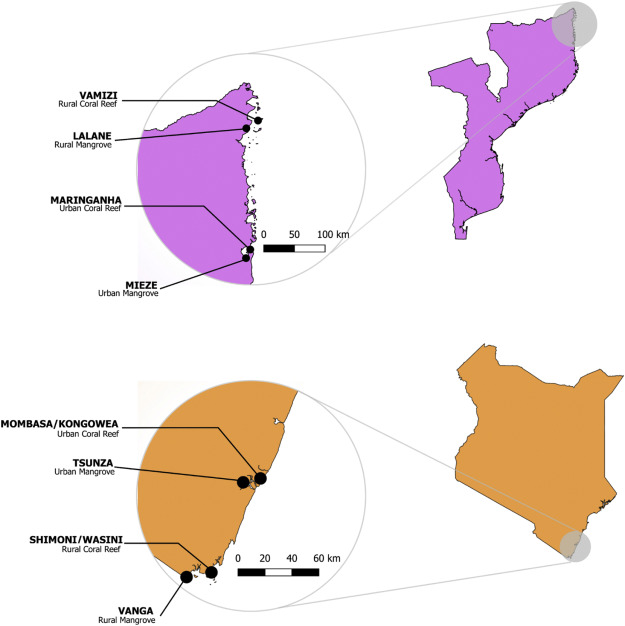

- Study looks at how coastal ecosystem services contribute to human well-being in eight coastal communities in Kenya and northern Mozambique

- A range of different datasets showed that women and men have different perceptions, values and access to ecosystem services.

- Acknowledging this gendered nature of ecosystem services could improve the development of socially just interventions

Whether you think we are from Mars, Venus or Earth, we all rely on ecosystem services, or the benefits we get from nature. However, gender is far from irrelevant.

In a paper published in the journal Ecological Economics, centre researchers Beatrice Crona and Tim Daw, along with colleagues from the UK and Mozambique demonstrate how men and women in eight coastal communities in Kenya and northern Mozambique benefit very differently from the ecosystem services they use and rely on.

Although gender inequalities connected to well-being are nothing new, this study provides a more nuanced understanding in the context of ecosystem services. Framed by perspectives such as ecofeminism and feminist political ecology, it goes beyond recording gender discrepancies, offering explanations for why discrepancies exist.

"This analysis exposes gendered trade-offs and reduces the risk of decision-making processes prioritising masculine values to the detriment of women," Beatrice Crona says. "It also highlights the need for a change of narratives when it comes to sustainable coastal livelihoods."

Highly gendered activities

The livelihoods of these communities are tightly interwoven with local ecosystems like mangroves, seagrasses and coral reefs. Activities such as fishing, pole cutting and farming are commonplace and some activities are clearly associated with one gender.

Men are more likely to take part in fishing and women are more likely to take part in seaweed collecting. Culturally defined roles for women and men in coastal tropical regions have led to women being confined to low income opportunities.

We found stark differences in how men and women use and experience ecosystem services,. Many social processes and structures underpin these gender differences.

Tim Daw, co-author

Female work considered secondary

In general, both men and women place higher value on items that they have harvested themselves and it’s not just about the economic value. In the mangroves, men form social relations associated with collective pole harvesting and house building, so they value poles highly. Whereas for women collecting firewood in the mangrove is an opportunity for autonomy, while the social interaction allows a space for the discussion of taboo topics between them.

When it comes to activities that provide income, such as fishing, things are a little different. Despite not being directly involved in fishing, women place very high value on fish, even though men capture most of the benefits.

“This gendered valorization suggests that both men and women see female work as secondary,” Beatrice Crona says, noting that similar gendered asymmetries exist for fish trading and tourism too.

Traditions and norms create gendered spaces

The sharing of ecological knowledge, for example on medicinal plants, is also gendered with older women teaching girls and older men teaching boys. Traditions and cultural norms create gendered spaces in the landscape and the sea. These spaces are also defined by behavioural expectations. For instance, men were constrained from activities like shell collecting, because that was considered as female.

Access to funds, transportation, skills and knowledge act as barriers in different activities. Formal and informal agreements also play a role in reinforcing gender divides in access. Patron-client relations in trade, for example, are dominated by men.

Based on their findings, the authors argue that deeper institutional reforms such as rights-based interventions are needed to allow women to benefit from ecosystem services.

“Understanding the role of gender in ecosystem services helps researchers and practitioners to avoid exacerbating biases, or enhancing gendered vulnerabilities, and to identify where interventions can make a difference,” they conclude.

Methodology

The SPACES project combined multiple methods to investigate the links between coastal ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Gender disaggregated data from these methods allowing for a diversity of perspectives on gendered aspects of ecosystem services. Multidimensional wellbeing analysis allowed participants to self-identify wellbeing benefits derived from the coastal ecosystems. Participatory qualitative methods such as photo voice, focus groups and participatory mapping were used understand the perception of gendered differences. These methods were combined with structured household surveys and an value-chain analyses for mangrove, fishery and tourism products to look at market structures. Findings were discussed using the ecosystem service-wellbeing chain conceptual model proposed in Daw et al 2016.

Link to publication

Fortnam, M., Brown, K., Chaigneu, T. et. al. 2019. The Gendered Nature of Ecosystem Services. Ecological Economics. Volume 159, May 2019, Pages 312-325. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.018

Beatrice Crona's work centers on various aspects of oceans and fisheries governance, as well as understanding different emerging global connectivities and their effects on social-ecological outcomes at multiple scales

Tim Daw studies the interaction between ecological and social aspects of coastal systems and how these contribute to human wellbeing and development.