There is a real need to better understand where and when nature delivers benefits in cities, according to a new study in Nature Sustainability. Photo: N. Ryrholm/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

URBAN NATURE AND HUMAN WELL-BEING

Context is key

When it comes to efforts to improve health and well-being of city-dwellers, same approach can have varying effects in different areas and with different groups of people

- There is a need to better understand where and when nature delivers benefits in cities, according to a new study

- The study focuses on ten key urban ecosystem services, including air quality, water supply, recreational opportunities, and mental health

- The authors emphasize the importance of considering social context, cultural preferences, and community voices in the prioritization and planning of urban nature

A tree is not just a tree. Adding them to concrete jungles certainly have their benefits but a belief it is a quick fix on issues like air pollution requires a rethink.

In a new Nature Sustainability review article, centre partners from the Natural Capital Project, an international project developing tools to account for nature’s contributions to society, explore the many social, ecological, and technological contexts that help determine the benefits of urban nature in cities worldwide.

"When our team started reviewing past work on urban ecosystem services, we saw a real need to better understand where and when nature delivers benefits in cities. Nature-based solutions - urban trees, rain gardens, et cetera - are being deployed at an accelerating pace without recognition of the key contextual factors that affect the success of these efforts," says lead author Bonnie Keeler, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

Same approach, varying effects

The review focuses on ten key urban ecosystem services, including air quality, water supply, recreational opportunities, and mental health. The main finding is that context is key: the same approach can have varying effects in different areas and with different groups of people.

For example, street trees can either improve or degrade local air quality in cities, depending on where they’re planted relative to sources of pollution. Rain gardens and stormwater retention devices work differently in cities with separated versus combined sewer systems

Lead author Bonnie Keeler

The authors summarized their findings in a series of research briefs, included as supplemental materials, designed to be used by practitioners interested in implementing nature-based solutions in their cities.

“The emphasis on practical guidance for planners and policy-makers makes this contribution unique” explains Keeler, “in addition to an academic summary, we included short reviews for each service designed illustrate the practical implications of the latest research”.

Equity is important

Equity also plays a critical role in determining where to implement nature-based solutions.

"Historically, urban nature has been deployed in ways that privileges some residents over others, leading to big discrepancies in terms of who benefits from urban nature.” says Keeler. The authors emphasize the importance of considering social context, cultural preferences, and community voices in the prioritization and planning of urban nature.

This emphasis on a tailored, local approach that considers multiple factors is different from what has been done in the past. Instead of focusing on single goals like mitigating air pollution or reducing carbon emissions, this synthesis suggests that city planners could benefit from investing in understanding the diverse contributions nature provides to people across all contexts in their particular city.

The researchers also call for more urban ecosystem services studies be done in the Global South and in lower-income countries, to add essential contexts that are currently missing in the current body of research. With this knowledge, leaders can make strategic decisions that deliver the greatest impact, maximizing nature’s value where it matters most.

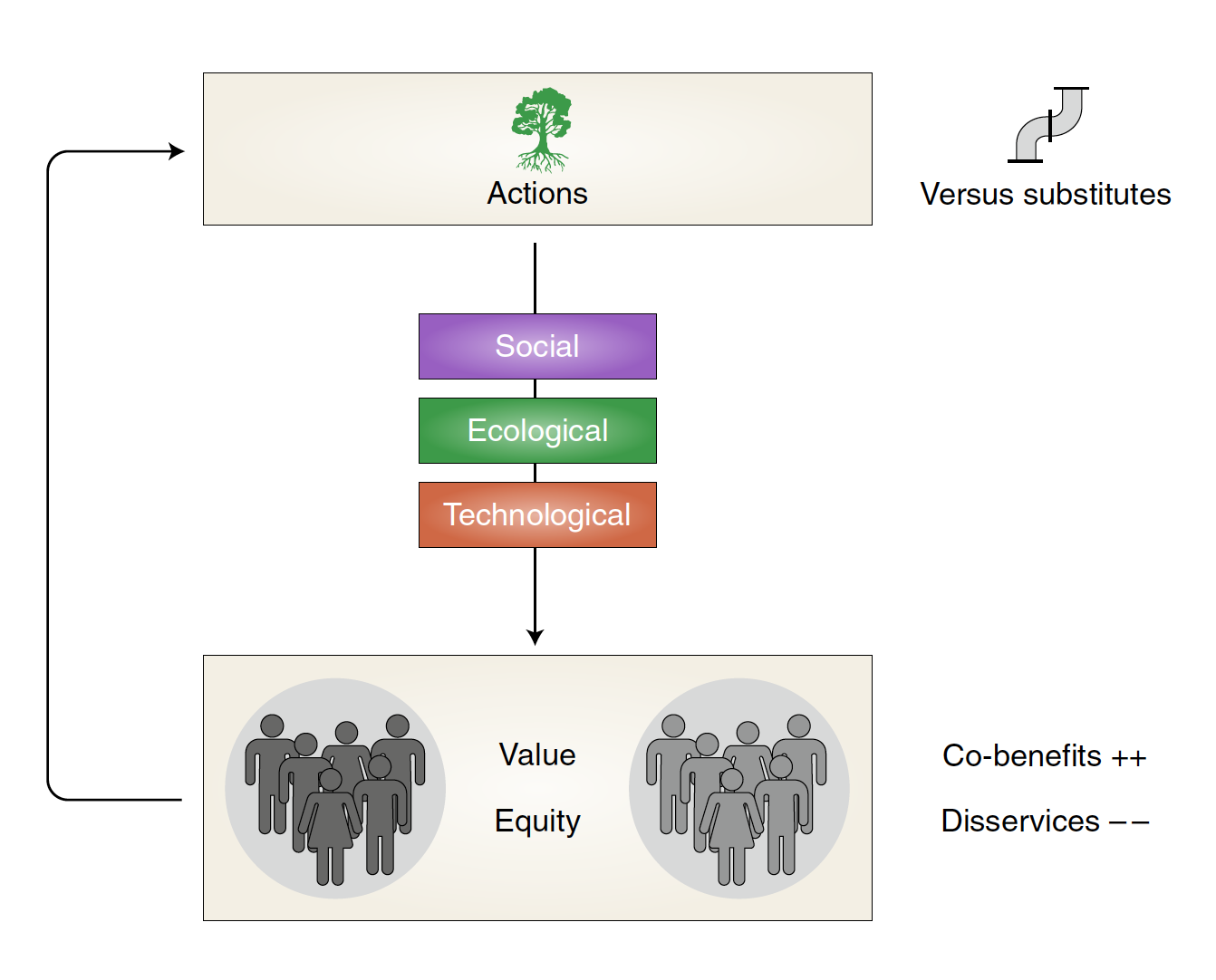

Actions lead to changes in the value of urban ecosystem services, defined by a change in human well-being, which may be different for different groups of people, hence the importance of considering equity.

Keeler, B.L., Hamel, P., McPhearson, T., et. al. 2019. Social-ecological and technological factors moderate the value of urban nature. Nature Sustainability volume 2, pages29–38.