Actors from diverse indigenous and scientific knowledge systems share experiences in a walking workshop in the Karen village of Hin Lad Nai in Chiang Rai, Thailand. One example of the Multiple Evidence Base approach in practice. Photo: P. Malmer

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

knowledge systems

Towards solving a key puzzle in the IPBES

New publication presents progress toward tools and approaches for working with diverse knowledge systems in ecosystem assessments

- Methods and tools for bridging different knowledge systems based on equity and reciprocity are needed in tackling the challenges of the Anthropocene

- The Multiple Evidence Base (MEB) approach is one such method, highlighted in the IPBES.

- Five tasks need attention to apply MEB thinking in practice while building trust, facilitating communication and allowing for a joint learning.

The Anthropocene is characterised by the complex interactions and feedbacks of human action and environmental change. In the face of this complexity, governing ecosystems for sustainability is no small feat, and it requires an “all-hands-on-deck” approach as far as knowledge mobilisation and production for necessary adaptation and transformation of social ecological systems is considered.

The need to combine insights from diverse knowledge systems for decision making and sustainable management of resources has been well recognised in science-policy platforms such as the Millennium Ecosystems Assessment and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and has received a new push for relevance in the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

However, methods and tools that guide assessments of knowledge beyond the local scale in ways that are equitable, transparent and generate useful outcomes for all are still sorely needed

A majority of the Earth’s surface is governed by Indigenous peoples and local communities. Producing and uncovering knowledge that is useful in sustainability efforts requires that knowledge systems are bridged in ways that are useful to, and does justice to, their efforts.

Indigenous and local knowledge systems represent ways of learning from and with the environment that present alternative to western-based science. These systems and the knowledge holders in them carry insights that are complementary to science, both in terms of scope and content, and also in ways of knowing and governing social-ecological systems during turbulent times and in articulating alternative ways forward. This is expressed in a Multiple Evidence Base (MEB) approach, developed by SRC researchers and SwedBio.

Achieving this kind of collaboration means we have to move from studies ‘into’ or ‘about’ indigenous knowledge systems, to equitable engagement with and among them

Going beyond Multiple Evidence Base

In a paper recently published in Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, centre researchers Maria Tengö, Pernilla Malmer, Thomas Elmqvist and Carl Folke, together with colleagues, identify five key tasks for knowledge system integration, building on the MEBase approach.

The five tasks form a framework that the authors hope will guide successful collaborations between indigenous and local knowledge and western science to enhance governance for sustainability.

The tasks aim to create space for different actors and institutions to take part in knowledge-sharing processes that are equitable and empowering, and the authors use case studies from the CBD and IPBES to discuss the framework.

“The framework we introduce is based on our experiences of practicing co-production of knowledge in a variety of processes, from local to global settings. It is also supported in the literature review we conducted,” Malmer explains.

An intricate fabric

The authors use the analogy of weaving to describe the process of bridging knowledge while respecting each knowledge system.

“Weaving allows each thread to maintain its integrity and at the same time it produces a fabric that can hold elaborate patterns, in a sense painting the bigger picture without losing the high resolution details” says Tengö. “The desired outcome of weaving knowledge systems is a collaboration that respects the integrity of each system.”

To do this, Tengö and her colleagues present five tasks needed to apply multiple evidence base thinking:

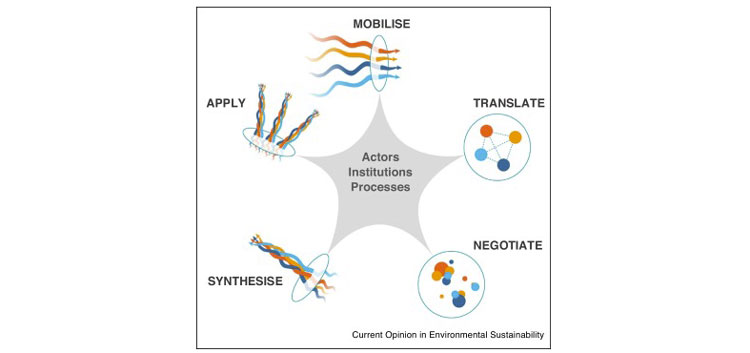

Conceptual figure illustrating how actors, institutions, and processes are at the core of the tasks required for successful collaboration across diverse knowledge systems

Mobilise means to articulate existing knowledge. In assessments such as the pollination assessment in the IPBES, indigenous and local knowledge is not available for science to interact with. The authors emphasize the need to mobilize knowledge in ways that uses mechanisms within the knowledge system to determine which knowledge is relevant – rather than to use validation mechanism from science. The need for mobilisation, and the time and costs it entails, have not been acknowledged within the IPBES.

Translate is about adapting the knowledge so that all actors can understand. This implies using a language that is understood by everyone and that there are interactions back-and-forth between actors to clarify their contributions in a respectful way – including contributions of scientific kinds of knowledge.

Negotiate means that actors from different knowledge systems interact to jointly assess where their contributed knowledge overlap, differ or are in conflict.

Synthesise means that the actors shape a broadly accepted common knowledge basis for a particular purpose. In ecosystem assessments, synthesis often implies that all knowledge is integrated into scientific knowledge, but the authors emphasise that they rather encourage collaborative approaches that allow for diversity and thereby foster mutual respect and broad usability and accessibility to knowledge.

Apply is when and how the common knowledge bases are used to inform decision-making and action in multiple contexts. For application to be successful it is crucial that the actors who are involved have the rights and mandates to implement new governance arrangements and take action based on the synthesised knowledge. In this way, application can provide learning that can feed back into the knowledge systems.

“The challenge of sustainably governing ecosystems in the Anthropocene will require effective collaboration. Achieving this kind of collaboration means we have to move from studies ‘into’ or ‘about’ indigenous knowledge systems, to equitable engagement with and among them,” Tengö concludes.

“We hope that these five tasks can contribute to designing processes for doing this in a way that builds trust, facilitates communication and allows for a joint learning across different knowledge systems.”

Tengö, M., R. Hill, P. Malmer, C. M. Raymond, M. Spierenburg, F. Danielsen, T. Elmqvist, C. Folke. 2017. Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—lessons learned for sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 26–27:17–25

Maria Tengö is a research leader of the Biosphere Stewardship stream at SRC, and is currently leading research projects on co-production of knowledge for syntheses across scientific, local and indigenous knowledge systems; sense of place and cultural ecosystems services in Southern Africa; and emerging stewardship networks in Bangalore, India.

Pernilla Malmer is an agronomist by training and holds a comprehensive professional experience of working with indigenous peoples organizations and networks, farmers' organizations, NGOs and biodiversity/agriculture networks in general, from local to global scales, in Sweden as well as in Latin America, Africa and Asia. Her expertise comprises agricultural biodiversity and farming systems, and the indigenous and local knowledge systems and cultures that are shaping and reshaping these, as well as the corresponding links to social-ecological resilience and human wellbeing.