A recent study compares 23 cases of participatory scenario planning, finding several benefits of the approach that can help build resilience, and identifying key challenges in improving the approach. Photo: J. Wadman/Azote

Scenarios planning

Setting the social-ecological scene for the future

Participatory scenario planning allows people to tackle complex environmental problems, but improvement needed

- 23 examples of scenario planning provides basis for guidelines to promot good practice

- The first study to compare social-ecological scenario studies

- Scenario planning boosts environmental management and scientific understandings

"Scenarios" are descriptions and visualisations of the potential future of a system. In participatory scenario planning different groups of people to use their local and scientific knowledge to develop sets of scenarios that provide multiple perspective on real-world social-ecological problems.

While scenario planning exercises have become increasingly applied in environmental research contexts over the past few decades, there is little research on how they actually affect aspects like social learning, innovation or empowerment.

Scenario work aims at informing policy and can impact many different stakeholders.

This makes participation a key aspect of these exercises in the realms of environmental research and natural resource management.

Scanning the field

A recent study by Garry Peterson, Tim Daw, Matilda Thyresson, Maike Hamann and diverse international colleagues, compares and contrasts 23 examples of participatory scenario planning.

The study, published in Ecology and Society, can help improve the rigor, inclusiveness and effectiveness of the exercises. This is increasingly important as global initiatives such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) are adopting the approach.

"Participatory scenario planning is increasingly used to explore ecosystem services in alternative futures. And we expect it will continue to increase within large scale initiatives such as the IPBES"

Garry Peterson, co-author

The paper results from a collaboration of 24 researchers from 23

research institutes around the world, a broad team developed through the PECS network.

Based on their review the authors believe that there are a number of practical guidelines which could promote good practices within the approach.

"We chose cases based on three criteria," explains Daw.

"The first was that those contributing with a case had first-hand experience of participatory scenario planning, the second that the cases were place-based and linked social and ecological factors. Thirdly we wanted ensure that cases were diverse in terms of the issues, ecosystems, and social situations they addressed."

Three main questions that were addressed in gathering experiences from the different participatory scenario planning cases were: How was it useful to participants and researchers? How did it contribute to decision-making? And what are common methodological challenges in the approach?

"This is the first study comparing social-ecological scenario studies conducted by different teams" says Thyresson.

"Consequently we had to develop a new framework to allow us to compare quite different cases to answer our questions."

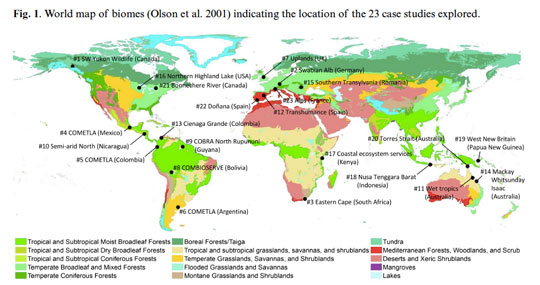

The 23 cases that were part of the study were chosen to cover many different types of systems.

Improving dialogue and engagement

The study found that participatory scenario planning is beneficial in many ways.

Across all 23 cases, stakeholder engagement was enhanced through the process. Scenario planning also supported the diversity, equity and legitimacy of environmental decision-making.

The approach was found to improve the quality of dialogue between stakeholders, help bring in different kinds of knowledge, and have the potential to support creativity and social innovation.

Scenario processes improved the ability of participants to embrace the complexity of uncertainty, surprise and contradictions. Hamann adds

"Since an understanding of complexity is a key strategy for enhancing and fostering resilience thinking, this finding supports the idea that scenario planning can play an important part in building resilience."

However, participatory scenario planning is time consuming, and the review identified three key challenges to the development of social-ecological scenarios.

A community for the future

Firstly, there is a need to carefully reflect on what and whose values are being promoted or supressed through the process. Though the process was often mostly explorative, investigating potential futures, there is a balance to strike between that and being normative, portraying futures that "should be."

Second, limited availability of resources and people to continue working in projects after the exercise is finished reduces the possibilities for evaluating and updating scenarios. However, revisiting and evaluating scenarios often substantially increases the quality and usefulness of these processes.

Thirdly, it is important but often challenging to navigate between the scientific and policy goals of scenario planning while also engaging with the local social-ecological context and different kinds of knowledge.

These challenges could be better navigated by creating a more connected and self-aware community of scenario practitioners, that enables people to engage with others to exchange experiences and knowledge, to build on past successes while avoiding problems.

"Based on our review we can see that participatory scenario planning has contributed to environmental management and improved scientific understandings," concludes Peterson.

"Scenario planning is well suited to respond to increasing demands for science that engages with diverse people to tackle complex problems, however to do this researchers need to develop new methods and a community of practitioners. Our hope is that this review might serve as a starting point for this."

Citation

Oteros-Rozas, E., B. Martín-López, T. Daw, E. L. Bohensky, J. Butler, R. Hill, J. Martin-Ortega, A. Quinlan, F. Ravera, I. Ruiz- Mallén, M. Thyresson, J. Mistry, I. Palomo, G. D. Peterson, T. Plieninger, K. A. Waylen, D. Beach, I. C. Bohnet, M. Hamann, J. Hanspach, K. Hubacek, S. Lavorel and S. Vilardy 2015. Participatory scenario planning in place-based social-ecological research: insights and experiences from 23 case studies. Ecology and Society 20(4):32.

Garry Peterson is Professor in Environmental Sciences with key focus on resilience in social-ecological systems. He uses complex systems theory, spatial analysis, and the synthesis of social and ecological data, to develop theory and practical understanding that people can use to better manage the ecosystems they live within.

Matilda Thyresson is a post-doctoral researcher at the centre. Matilda is a part of the Sustainable Poverty Alleviation from Coastal Ecosystem Services project (SPACES) investigating the relationship between coastal ecosystems in Kenya and Mozambique and the wellbeing of poor people living along the coast.

Tim Daw studies the interaction between ecological and social aspects of coastal systems, their governance, the ecosystem services they provide, and how these contribute to coastal people’s wellbeing.

Maike Hamann is a PhD student at the centre, exploring the links between ecosystem services and human well-being in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Her work is part of a programme on the 'Governance of ecosystem services under scenarios of change in southern and eastern Africa'