Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

REFLECTIONS ON COVID-19

Conflict and collaboration in pandemic times

Can current management of Covid-19 learn from how countries have dealth fisheries conflicts? Network analysis can help reveal why some actors choose to pick a fight while others want to collaborate. Photo: G. Hyzak/U.S Coast Guard

- Many potential conflicts have instead boosted collaboration

- Answers to why actors respond the way they do can be found in the extent to which they are already collaborating or stuck in conflicts with others

- Network analysis helps study patterns of relations among actors in greater detail

How network analysis can help understand why some actors choose to pick a fight while others want to collaborate

DISCLAIMER: This reflection presents insights that are relevant to the discussions related to both the causes for the pandemic and the solutions needed to build a more resilient, global society. Covid-19 affects all aspects of our lives, we want to help make sense of this tragedy, in empathy with all those suffering from it.

EACH TO THEIR OWN? The corona crisis arose quickly and unexpected. After an initial stumbling period where the magnitude and severity of the crisis was sinking into our collective consciousness, many governments acted swiftly with more or less draconian measures to stop or at least reduce the spread of the virus.

But did they act as a collective of collaborating states or more like individual countries left to their own destiny?

Clearly more toward the latter, at least initially.

How could this happen in Europe which is supposed to be a focal point for interstate collaboration?

There are multiple reasons why countries or other stakeholders resort to either conflict or collaboration. Historical ‘baggage’ is one. Uncertainty and fear are two others.

Tension over fish stock management

Conflict research has long distinguished a cause for a potential conflict from actual conflictual behaviour.

Indeed, many potential conflicts have instead boosted collaboration.

For example, multiple states with stakes in a common resource, such as a fish stock, might decide to join forces to protect the stock from overfishing. The relative success of the regional fishery management organization The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in reducing Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing in the Southern Ocean serves as a good example of such collaborative effort.

But the Atlantic mackerel dispute shows how a similar setting could also spur states to engage in conflict. The dispute started in 2007 when Icelanders started fishing mackerel in their own waters. This was a point of tension for EU and Norwegian fishers whom believed that mackerel exclusively belonged to their quotas. However, their reluctance to revisit “total allowable catch” mackerel quotas fuelled Iceland’s discontent with the EU and Norway.

Such conflicts could escalate into navy vessels attacking fishing fleets from the other state, although in this case the conflict stopped before that.

Why they do what they do

As expected, there are multiple reasons why countries or other stakeholders resort to either conflict or collaboration. Historical ‘baggage’ is one. Uncertainty and fear are two others (it certainly appears so in the handling of the current crisis).

Assume state A respond to an upcoming crisis by closing its border to state B, and potentially also shutting down ongoing trade agreements.

How should state B respond?

If state B has well-established relationships with many other states, it might think it can ‘afford’ to engage in a tit for tat conflict with state A. B might even drag other states into the conflict.

On the other hand, if state A and B share strong and collaborative relations with others (states C and D), B might respond with much less hostility to avoid creating further unbalances in this larger set of states.

In other words, closing borders goes against the overarching collaborative relationships that connect states A, B, C and D.

Having many common allies would likely have prevented state A from instigating non-cooperative measures in the first place.

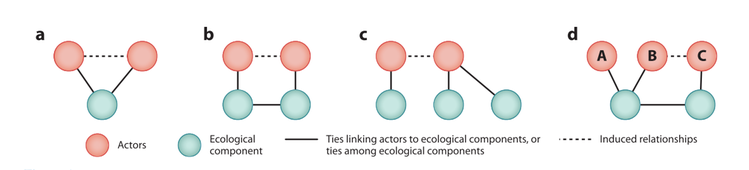

In figure A, two actors have stakes in a common resource. This relationship can trigger either collaboration or conflict. B is similar to a, but the actors have stake in two separate resources, although the resources are interdependent. This interdependency means that what the actors do with "their" resources have implicataions for other actors, thereby inducing indirect relations between them. D describes more elaborated versions of this kind of indirect relations, wheras C depict how inbalances between two actors in terms of how many resources they have access to creates a relationship that can trigger either collaborative or conflictual behaviour. The figure is taken from a study published in Annual Review of Environment and Resources. Click here to access the publication.

The role of network analysis

Discussions like these suggest that the answers to why actors respond the way they do can be found in the extent to which they are already collaborating or stuck in conflicts with several others.

This is where network analysis comes in.

Through such analysis we are able to study patterns of relations among actors in greater detail, how they relate to each other and others and how all this interaction expands into a wider net of actors and entities.

This can help shed some light on why some actors choose to pick a fight while others want to collaborate

Scientific background:

Bodin, Ö., M. M. García, G. Robins. 2020. “Reconciling Conflict and Cooperation in Environmental Governance: A Social Network Perspective.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 45 (1): (online first).

For more information, contact Örjan Bodin or María Mancilla García below: