In a study of participatory forums in Brazil and Peru specifically linked to how to manage water basins, researchers found that discussions required a high level of expertise and technical knowledge. If participants did not express themselves in expert terms, they remained excluded. Photo: Comitê Médio Paraiba do Sul website

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

PARTICIPATORY FORUMS

Learning the tech-talk

By expressing their interests in technical terms, previously excluded actors are able to gain influence and have their voices heard. Others remain marginalised

- Study looks at power relations, discourses and participation in four participatory forums in Brazil and Peru, specifically linked to how to manage water basins

- Discussions revolved around issues that required a high level of expertise and technical knowledge which is not equally distributed among the forum participants

- While the forums opened up for more participants beyond traditionally powerful actors, it was under the condition that they express themselves in technical terms

Participatory forums are meant to be democratic arenas where citizens, policy makers, experts and other interests meet to discuss and decide on important issues that concern them all.

That is the theory at least.

In reality, that goal is frequently challenged. While some studies have identified potential upsides of participatory forums, such as empowering and engaging a broad set of stakeholders, others have noted they can be used maintain established power structures, or even exclude certain stakeholders.

In a study published in Global Environmental Change, centre researchers María Mancilla García and Örjan Bodin have studied four participatory forums in Brazil and Peru specifically linked to how to manage water basins.

Diverse levels of involvement

Mancilla García and Bodin interviewed forum participants in four water councils in Peru and Brazil (two in each country) about their perceptions and experiences of participation.

The researchers’ choice of cases allows for an interesting comparison since forums in the two countries operate under different mandates and powers. In Brazil, basin forums have formal decision-making powers whereas in Peru they only have an advisory role to more formal government institutions. Moreover, water is managed differently in the two countries. In Peru, water has traditionally been the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture. In Brazil, the river studied is located in a traditionally industrial region, where private users have had a key role in shaping the management of the system.

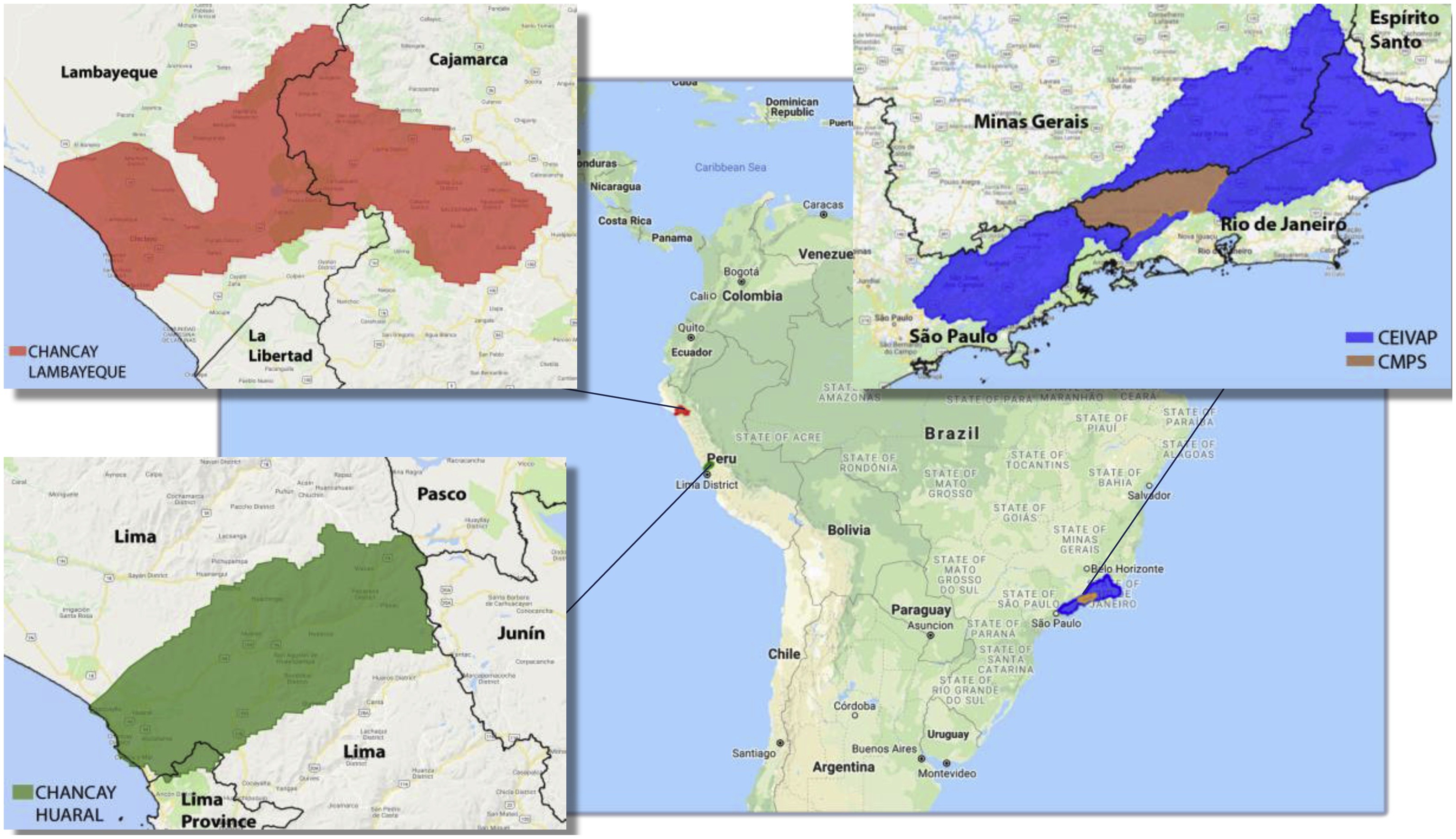

Map of selected cases. Design: A. Nascetti, base map Google Maps

Mancilla García and Bodin’s data reveal that discussions revolved around issues that required a high level of expertise and technical knowledge. The access to such technical knowledge is not equally distributed among the forum participants. In the case of Peru, peasant communities remained largely excluded from the discussions because their technical knowledge of water management is limited.

"One of the Peruvian participants explained he felt misplaced to share his view about water," explains Mancilla García. "He rather felt accompanying the process, as a spectator."

However, in Brazil the authors found that the most influntial actors included people beyond the usual suspects – such as government entities or large private users. “The long-term stable presence of water governance institutions (…) guaranteed access and exposure to technical knowledge and, by extension, fluency in expert discourses (…) This constitutes a significant change in accessing knowledge, brought about by institutional change” the authors conclude.

No place for non-technical talk

Some participants were not comfortable using technical terms and expert language, which prevented them from actively participating in the discussions or led them to decline participating in the councils altogether

This, says Mancilla García, raises questions about under which circumstances the forums actually serve the purpose of facilitating discussions and exchange of differing perspectives or when they risk being just another platform for powerful and established interests.

Since perspectives need to be framed in technical terms, Mancilla García and Bodin consider it “improbable” that participatory forums set as technical platforms can actually accommodate an equal amount of space for differing views.

While different discursive practices such as those put forward by various engineers seemed to find a place in the forum discussions, it was as long as they could be articulated within expert discourses. Other perspectives, such as indigenous communities in the Andes for whom water is not necessarily conceived as a resource to manage but rather as part of an understanding of their own identities and practices, did not find such a place.

The authors argue that while the forums opened up for more participants beyond traditionally powerful actors, it was under the condition that they express themselves in expert terms. If they did not, either because they lack the knowledge to do so or because their understandings of the issues at stake do not fit in the categories imposed by the ‘real’ experts – they remained excluded.

"Although some actors find ways to navigate the limitations imposed by the dominance of technical discourse, bridging the political and technical divide to ensure meaningful participation of all is a challenge yet to be met," they conclude.

Methodology

This study is part of a larger project investigating the strategies adopted by actors and networks of actors across multiple water governance forums. The data used for this article were collected through interviews and observation notes produced during seven months of fieldwork in Peru and Brazil. Four basin forums were selected for this study, two in Peru and two in Brazil. All participants in the four selected Water Basin Councils were included in the sample, provided that they had attended at least two meetings of the last six meetings the council had held. The data were analysed through an abductive approach applied to thematic analysis which led to the development of a coding scheme. The coding of the data was performed using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo11, and was applied to the interviews and observation notes.

García, M.M, Bodin, Ö. 2019. Participatory Water Basin Councils in Peru and Brazil: Expert discourses as means and barriers to inclusion. Global Environmental Change Volume 55, March 2019, Pages 139-148. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.02.005

Maria Mancilla-García, a PhD student, focuses on relationality in social-ecological systems, including network analysis and theoretical work on the concepts of intertwinedness and dynamism.

Örjan Bodin combines and integrates methods and theories from several scientific disciplines to develop better understanding of social-ecological systems