Centre researcher Tim Daw introduces the concept of ecosystem services elasticity to describe how human wellbeing changes in response to changes in ecosystem services.

Ecosystem services

Environmental change - who cares, who benefits,

who loses?

Introducing "ecosystem services elasticity" to untangle the relationship between ecosystems and human wellbeing

- Ecosystem services elasticity describes how human wellbeing changes in response to changes in ecosystem services.

- The conceptual framework helps identify critical points of intervention for poverty alleviation efforts.

- Understanding ecosystem services elasticity can contribute to the success of natural resource management.

In social-ecological systems research the focus is on people as well as nature and the aim is to promote both ecosystem health and human wellbeing. Ecosystem services is increasingly recognized as the benefits people obtain from nature, but we still have a poor understanding of how they actually enhance the many dimensions of wellbeing, and of how wellbeing is affected by changes in ecosystems.

In a study recently published in Ecology and Society, centre researchers Tim Daw, Beatrice Crona and Björn Schulte-Herbrüggen together with a team of international collaborators on the SPACES project introduce the term “ecosystem services elasticity” to describe how human wellbeing changes in response to changes in ecosystem services.

“Typically the concept of ecosystem services alludes to a positive relationship between the health and quality of ecosystems and human wellbeing. But the relationship in reality is not necessarily so clear-cut,” says Daw.

“For example successful conservation efforts might have a negative effect on some people’s wellbeing if a resource that they depend on and use becomes protected and off-limits. Meanwhile, imagine an ecosystem that is being degraded. This might be devastating for some people who rely on it and have no alternative, while others may be relatively unaffected.”

The term elasticity refers to how sensitive one variable is to another and is more often used by economists: for example the price elasticity of demand refers to how the demand for a product changes depending on changes in price. For ecosystem services, Daw and his colleagues use elasticity as a lens for looking at how human wellbeing changes in response to increases or declines in the quality of ecosystems.

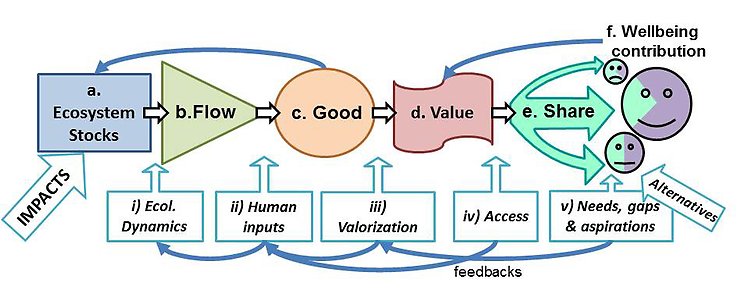

The authors introduce a conceptual framework as a tool for looking at what processes and factors lead to high or low ecosystem services elasticity.

From ecosystem stocks to individual wellbeing

The framework is made up of a number of elements that link ecosystems to human wellbeing, as shown in the figure above. “Ecosystem stocks” are the biophysical reality of ecosystems, the natural capital, what the authors refer to as “flows” represents the biophysical processes that are generated by the stocks and are potentially useful to humans.

“Goods” are the experiences or products from ecosystems that are valued by humans, they are not solely biophysical but are co-produced from flows by human inputs such as labour or the presence of people who appreciate the flows. The “value” of these to society is determined by societal processes such as cultural norms and markets. Many studies aim to represent the value of ecosystem services by calculating their money value.

However, since wellbeing is an individually experienced quality “share” refers to how the goods and value derived from ecosystems are then distributed among people depending on for example who has access to them and to what degree. “Wellbeing contribution” lastly reflects how an ecosystem service actually affects the wellbeing of an individual or a group of people depending on their individual situation and needs.

The case of the Kenyan fishmonger

The authors apply this framework on five different examples of coastal ecosystem services in East Africa and discuss the challenges and complexity that they uncover along the way. For example they look at the livelihood opportunities for female traders in the highly gendered costal Kenyan fishery.

Women are here not allowed to take part in the fishing activities, instead their main role is buying, frying and selling low-value fish to local consumers. When catches are low competition for access to fish is high. Male traders tend to have greater access to capital and therefore get first dibs on the bigger, more valuable fishes.

Protected areas, regulation on fishing gear and restrictions on fishing have served to increase catch rates, fish size and profits for individual fishers and led to improvements in ecological status. However, since these changes have led to lower catches of cheaper fish these efforts might at the same time negatively impact women’s livelihoods.

This is given as an example of low ecosystem service elasticity where the critical points for interventions, to avoid negative effects on the wellbeing of female traders, are in the “value” and “share” links.

“This framework can help us unpick the relationship between ecosystems and human wellbeing, finding the critical points which underlie how they relate to one another,” says Daw. “This way we can understand how vulnerable people are or are not to changes in the environment and identify opportunities and possible points of interventions in order to improve wellbeing.”

This research results from the project Sustainable Poverty Alleviation from Coastal Ecosystem Services (SPACES) project number NE-K010484-1, funded by the Ecosystem Services for Poverty Alleviation (ESPA) programme.

Daw, T. M., C. Hicks, K. Brown, T. Chaigneau, F. Januchowski-Hartley, W. Cheung, S. Rosendo, B. Crona, S. Coulthard, C. Sandbrook, C. Perry, S. Bandeira, N. A. Muthiga, B. Schulte-Herbrüggen, J. Bosire, and T. R. McClanahan. 2016. Elasticity in ecosystem services: exploring the variable relationship between ecosystems and human well-being. Ecology and Society 21(2):11.

Tim Daw studies the interaction between ecological and social aspects of coastal systems, their governance, the ecosystem services they provide, and how these contribute to coastal people’s wellbeing.