Sustainable diets

Centre report assesses criticism of Nordic Nutrition Recommendations

A new report lists four policy recommendations to ensure that the uptake of the new NNR is not hindered by unscientific criticisms.

Including environmental considerations in the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations has received much praise from authorities and scientists. But it has also sparked criticisms. Centre expertise clears the confusion in a new policy report.

- Some stakeholders, especially meat and dairy groups and farming organizations, have criticised the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations

- While some legitimate points of concern were raised, the authors of a new policy report found several scientifically incorrect arguments

- Concerns and fears apparent in these criticisms should be taken seriously, yet it must be acknowledged that dietary guidelines are not the best way to address all concerns across food systems

For the first time, the Nordic Nutrition Recommendation (NNR) has come with suggestions for a diet that is good not only for healthy people but also for a healthy planet.

This has received praise from many stakeholders, and the reception of the new recommendations has been positive from authorities and leading scientists.

But some stakeholders, especially meat and dairy groups and farming organizations, have pushed back.

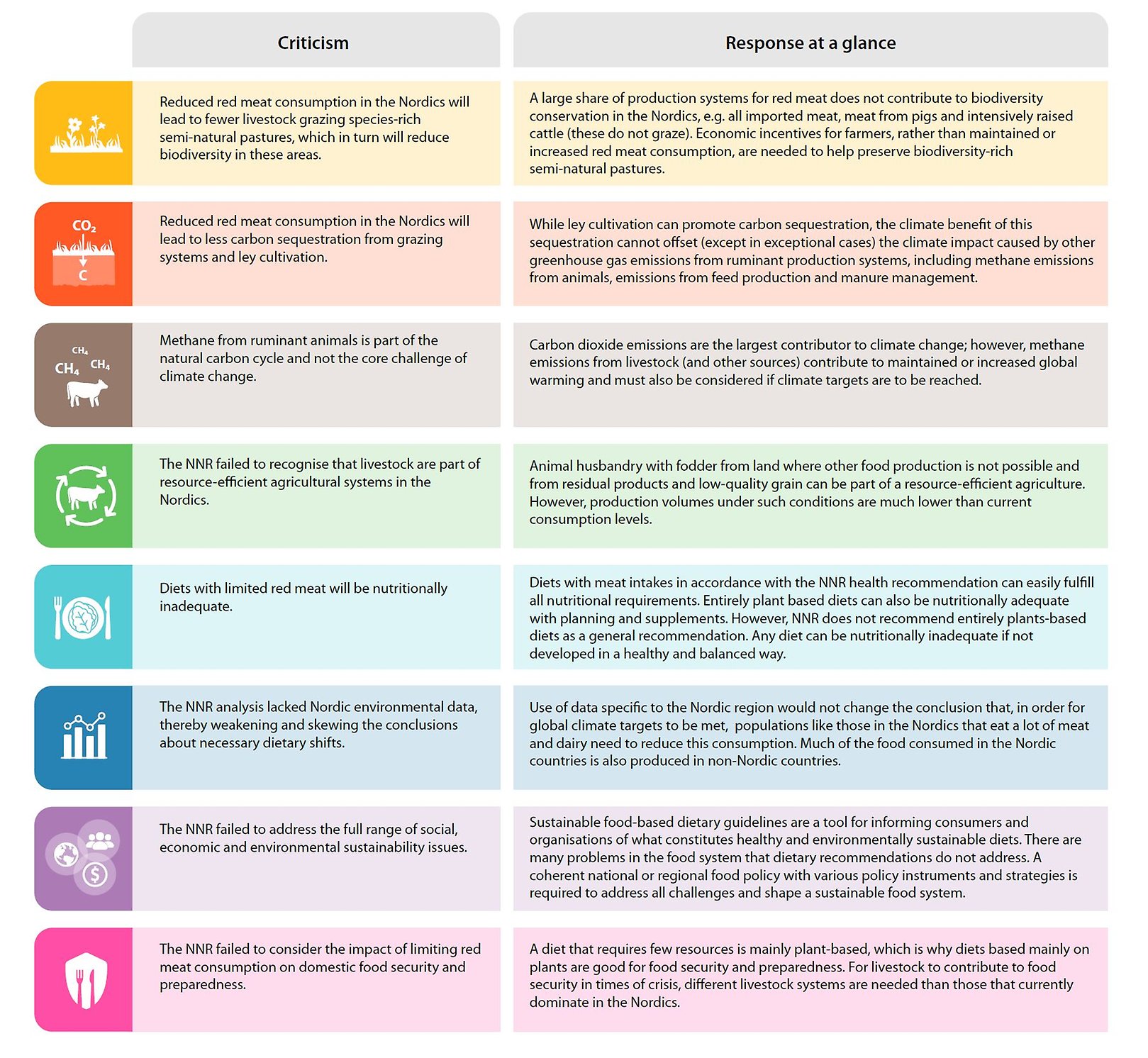

A new policy report authored by Centre researcher Amanda Wood and colleagues from Swedish University of Agricultural Science, and University of Helsinki, has taken a closer look at eight common criticisms to the environmental analysis in the NNR.

When going through the criticisms one by one, we can see that many lack substantial scientific support, and policies need to be built on facts.

Centre researcher Amanda Wood

While some legitimate points of concern were raised by stakeholder, the authors found a number of scientifically incorrect arguments.

“When going through the criticisms one by one, we can see that many lack substantial scientific support, and policies need to be built on facts,” comments Amanda Wood. She continues:

“We recognise that the issues raised by stakeholders extend well beyond the mandate of dietary guidelines. We should take the concerns and fears apparent in these criticisms seriously, yet acknowledge that dietary guidelines are not the best way to address all concerns across food systems.”

The report lists four policy recommendations to ensure that the uptake of the new NNR is not hindered by unscientific criticisms:

- National authorities and politicians should be aware of common misunderstandings and fallacies and base official advice on a solid scientific basis.

- National authorities should take forward the NNR’s environmentally-focused recommendations when updating national guidelines.

- National authorities could more clearly define what it means to recommend “considerably lower” red and processed meat intake for environmental reasons.

- The next NNR Committee should consider ways to more deeply and clearly embed environmental sustainability into the NNR food-based guidance in coming versions.

Zoom image

Zoom imageThe infographic summarises the eight common stakeholder criticisms that are explored in the report.

Rebuking the main critique

A lot of the criticism towards the environmental analysis in the NNR is aimed at their recommendation to reduce red meat consumption to considerably less than 350 grams a week to reduce environmental impacts.

This is based on sound science, according to the policy report.

A common concern was how to conserve biodiversity in semi-natural pastures if we consume (and produce) less red meat. Yet reduced red meat consumption does not mean that fewer livestock will graze in the Nordic countries, since domestic consumption and production are not directly and inevitably linked. For example, a lot of the red meat that is consumed in the Nordics either has not been produced here or has been produced intensively, i.e. without pasture grazing, meaning reduced consumption of these meats would not impact local grazing.

Stakeholders also critiqued the way methane was assessed in the NNR and highlighted the carbon sequestration potential of livestock grazing systems. But in nearly all cases, ruminant livestock emit more methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, than can be sequestered in their grazing systems.

Another argument to keep eating (and producing) meat was that livestock systems are resource efficient. Although livestock production can be resource efficient, many current systems in the Nordics use crops that could be eaten directly by humans or forage produced on land which could have produced food for humans at much more efficient rates.

Livestock’s role in times of crisis was highlighted by some stakeholders, but for livestock to promote food security in crisis it would require different livestock systems than the ones commonly in use in the Nordics.

Read the full report in English or in Swedish.

Clearing the confusion - A review of the criticisms relating to the environmental analysis of the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023

.jpg)