Anthropocene

The best way to deal with shocks is by combining diverse responses

The containership Ever Given was stuck in the Suez canal in March 2021. Photo: Anja Vrečko/European Space Imaging via Flickr.

Humankind’s best chance to deal with looming turbulences and crises is by diversifying response strategies

- Humanity is on its way into an era of uncertainty and turbulence

- The key to meeting this uncertainty is to increase the diversity with which societies can meet disturbances

- Instead of looking for the “best” practice of doing something, one should recognize that it’s a diversity of practices that might be best in the long run

Societies, economies and cultures are becoming increasingly interlinked globally. But the links are often rigid and vulnerable to shocks.

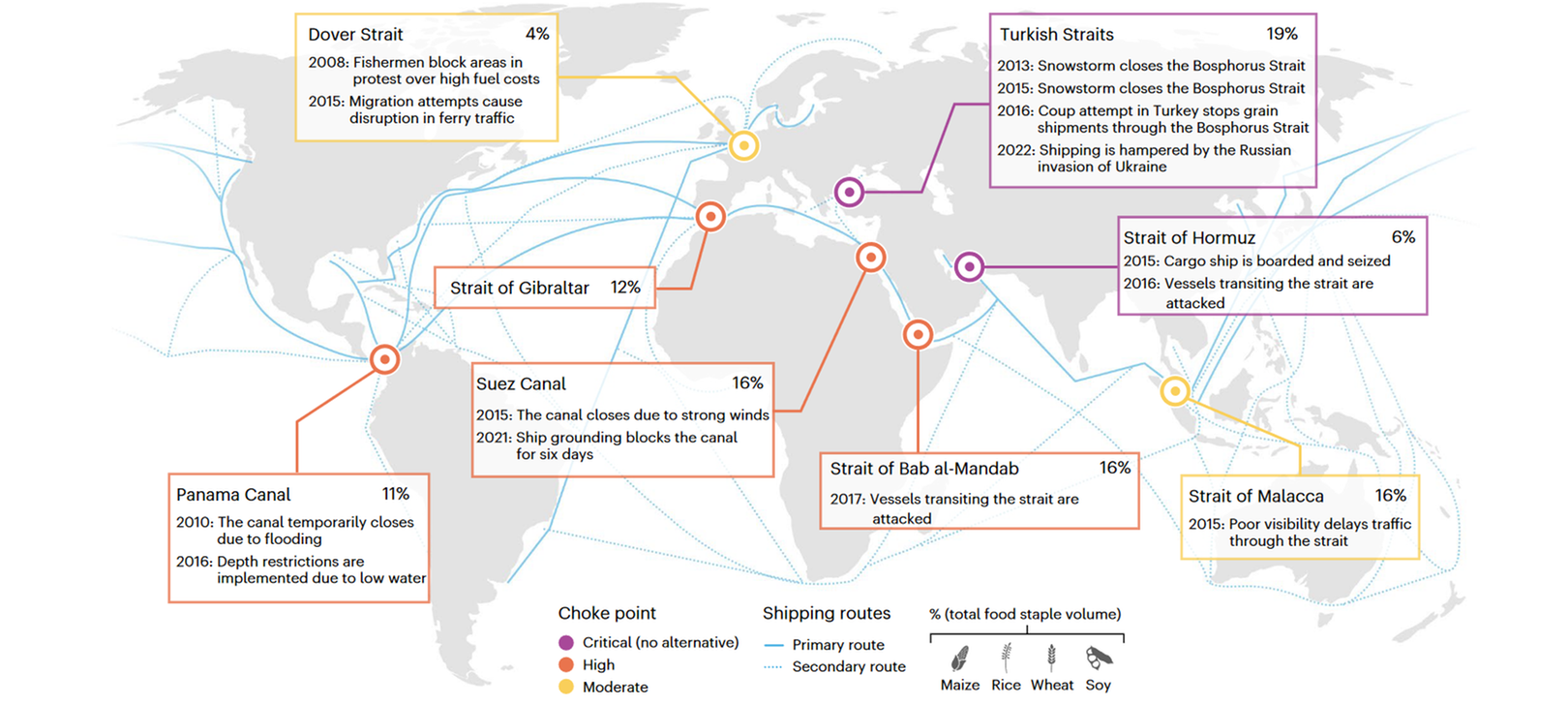

One example of such a fragile link is the Suez Canal in Egypt. On average, more than forty ships pass it daily to transport up to a billion tons of cargo from Asia to Europe and vice versa each year. 16 per cent of all shipped global food staples pass through this bottleneck.

So, when the Ever Given, one of the world’s largest container ships, ran aground in March 2021 and blocked the canal for almost a week, the consequences were severe.

Linked but not flexible

The story of the Ever Given is but one of many examples of how small disturbances can cascade into large consequences in the rigid web of links of the modern world.

Humanity is on its way into an era of uncertainty and turbulence. The multiple global crises that have manifested over the past years, be it food crises, the coronavirus pandemic, climate change or the war in Ukraine, are part of this turbulence.

Response diversity cannot be taken for granted and must be actively designed and managed.

One of the lead authors Anne-Sophie Crépin from the Beijer Institute at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and Stockholm Resilience Centre

While some crises can be anticipated, others strike unexpectedly. How then can societies become more resilient towards shocks that cannot be predicted?

The key is to increase the diversity with which societies can meet disturbances, argues a group of scientists, including centre researchers Anne-Sophie Crépin, Magnus Nyström, Erik Andersson, Thomas Elmqvist, Cibele Queiroz and Carl Folke, in an article published in Nature Sustainability.

Spreading the risk

“Response diversity cannot be taken for granted and must be actively designed and managed,” says one of the lead authors Anne-Sophie Crépin from the Beijer Institute at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Responses can be diversified spatially or temporally. For the Ever Given-incident, a spatial response would have been using alternative shipping routes, and a temporal one to have larger storage capacities at the destination which can be used to even out availability over time.

Major maritime choke points and primary (solid blue) and secondary(dotted blue) shipping routes.

Maintaining response diversity comes with two main challenges though:

- There is a trade-off between using resources in the best way now and investing them to better deal with potential unexpected future change.

- Different shocks require different responses. Thus, decision-makers must balance trade-offs between which sorts of disturbances to prepare for.

Awareness of these trade-offs but also of the importance of response diversity itself is an important first step.

“Such fundamental design considerations, the cost of response diversity and the necessary compromises in addressing the question of ‘resilience of what to what’ must play key roles in strategies for strengthening response diversity,” says centre researcher Magnus Nyström who is one of the lead authors of the study.

A next step could be to look for win-wins, situations where response diversity can be enhanced without extra costs.

Enhancing response diversity also requires a shift in mindset. Instead of looking for the “best” practice of doing something, one should recognize that it’s a diversity of practices that might be best in the long run.

Seven tentative principles to develop policies across ecological, social and economic domains

- Recognize that risks can be reduced with a variety of tools in the toolbox.

Having different ways of responding to the same or different kinds of disruptions confers resilience. Apparently redundant elements or processes can in fact be response diversity, enabling the system to perform the same function in different ways with different responses to different kinds of disruptions. - Acknowledge that the useful set of tools is context-dependent.

Responses differ in terms of their spatial, temporal and functional scales, and they include substitutable, complementary and compensatory options. - Account for the social benefits of having a toolbox with a variety of tools, which are otherwise ignored in private exchange.

Economic efficiency—getting more for less through market exchange—can ignore the social benefits of maintaining different tools. The cost of creating or maintaining response diversity leads to its erosion through efficiency drives, thereby increasing the potential costs of a lack of response diversity. - Account for multiple scales when choosing which tools to use.

There are trade-offs between response diversity at multiple scales in space and time. For example, increasing different sources and kinds of supplies at a large scale can lead to a decline in the variety of local-scale sources; if individual banks (local scale) use similar risk-management models, homogeneity in responses is cultivated within the sector as a whole (global scale). - Recognize that tools are interdependent.

Different responses to different disruptions may intersect with or influence a reorganization process in different phases and in different (complementary or contradictory) ways. - Be flexible in which tool is the best over time.

Optimizing response strategies to the current pattern of disruption can be detrimental if the pattern of disruption changes. Two examples are ignoring climate change and not considering multiple potential disruptions in supply chains. - Account for how a tool can create moral hazard (unintended behavioural responses).

Support to maintain function in risky environments can lead to increasingly risky behaviour or unequal, disproportionate costs and loss of response diversity. A classic example is insurance in agriculture.

Source: Walker, B., Crépin, A.-S., Nyström, M., et.al. 2023. Response diversity as a sustainability strategy. Nature Sustainability.

Walker, B., Crépin, A.-S., Nyström, M., et.al. 2023. Response diversity as a sustainability strategy. Nature Sustainability.

.jpg)