RESEARCH PROFILES

Getting to grips with the complexities of human behaviour

Caroline Schill will co-lead the new Interacting Complexities theme at the centre.

Caroline Schill on how there is more to humans than the rational mind, and why researchers studying human behaviour should care about complexity perspectives

- In 2020, the centre introduced new research themes to reflect a shift in its research focus

- One of the new theme leaders is Caroline Schill, who will co-lead the new Interacting Complexities theme

- Schill's research focuses on human behaviour in complex and intertwined social-ecological systems

Considering people and nature as deeply intertwined and co-evolving is foundational to the centre’s research. To capture, understand and gain insights about the complexities of these dynamic interactions, centre researchers use complexity-based approaches to study social-ecological systems.

The centre’s research theme on this topic, Interacting Complexities, is under new leadership. In this interview, Caroline Schill talks about her work on human behaviour and collective action for sustainability, as well as her ambitions for this important theme which operates at the core of social-ecological systems research.

Caroline, you work on human behaviour in social-ecological systems. Why is this important?

We’re in the age of the Anthropocene, where humans are the main force of change on the planet. Urgent action is needed, including substantial changes in human behaviour. But our approach to understanding this behaviour remains reliant on overly simplistic models and barely takes into account this ‘new’ reality in which we live.

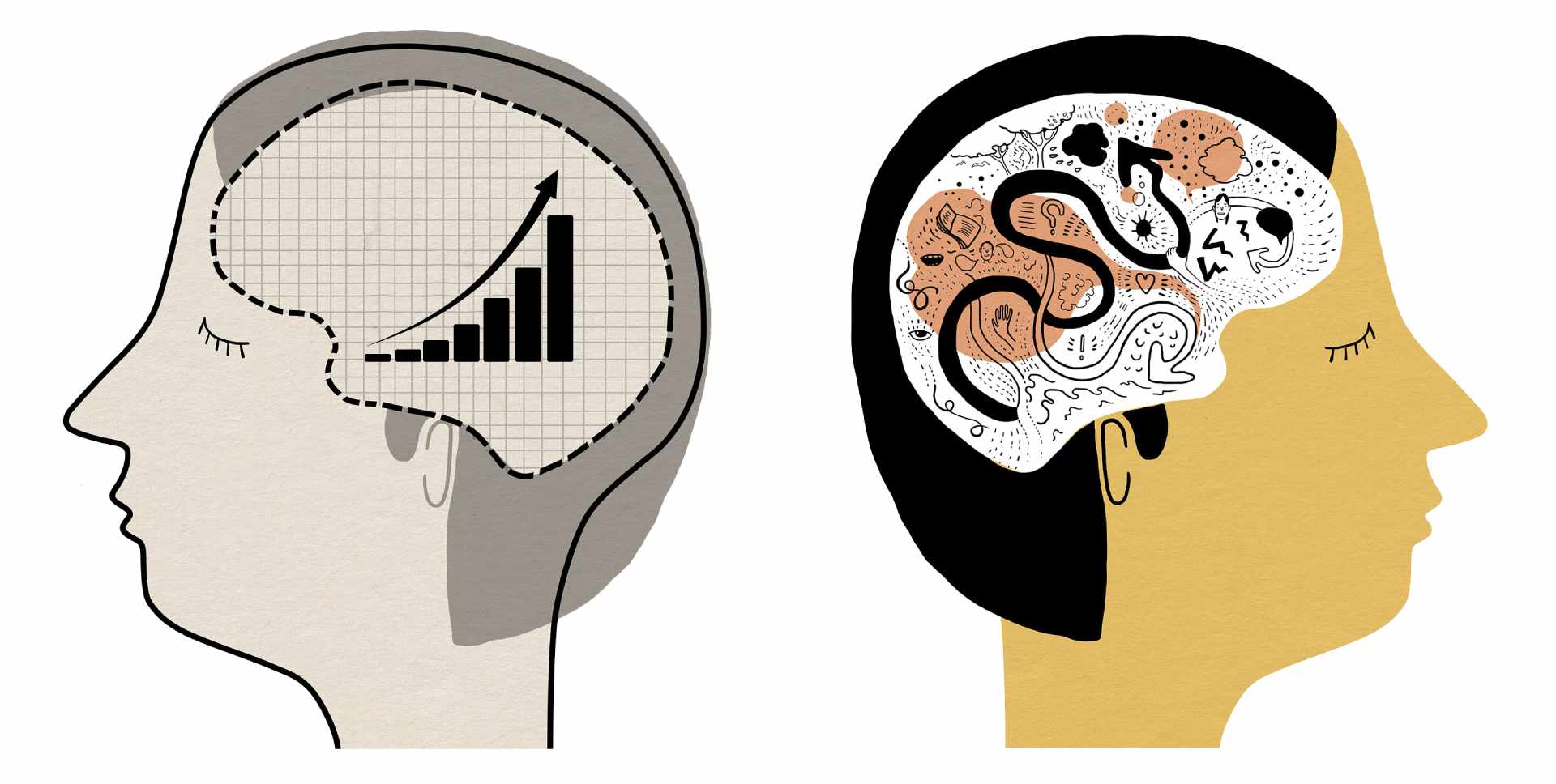

Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote

Policy making still often relies on the idea of humans as homo economicus, the figurative human characterized by its infinite ability to make rational and self-interested decisions. We know this is not an accurate representation.

Humans and their environments are deeply linked. We shape and are shaped by the social groups and broader socio-cultural and biophysical contexts we find ourselves in. We actually know little about human behaviour in relation to social-ecological change, but it is essential to inform policy and action towards sustainability.

Your work also looks at how we collectively respond to ecological regime shifts. Can you tell us about this?

Regime shifts are large, abrupt and long lasting changes in the structure and function of systems. When this is an ecosystem, for example, such changes can have disastrous consequences for the people who rely on them for their livelihoods.

There is this idea that we can prevent regime shifts by understanding the state of the system and providing people with knowledge about what to do to avoid or reverse it. But this is not enough when it comes to shared resources that require collective action to obtain a certain outcome.

Most challenges we face in the sustainability space can be characterised as collective action problems. We would all benefit from a certain action (for example emitting less carbon), but individuals or small groups on their own have little or no incentive to change their behaviour.

If we want to progress towards more sustainable ways of being and living we need to understand how we can make collective action work in the face of environmental change - be it at the level of communities, cities, countries, or regions.

You’re currently looking at these collective action problems in small-scale fisheries. How?

We have a good idea about the causes and consequences of ecological regime shifts. But how people actually respond to regime shifts is less understood. Take for example exhausted and unproductive fishing grounds. Due to the heavy reliance of millions of households on small-scale fisheries, marine regime shifts could threaten a huge number of livelihoods.

If fishers knew their actions would lead to huge changes that threatened their livelihoods, would they change their behaviour? We work with communities in Colombia and Thailand to study how people behave in situations like these.

We have also designed so-called common-pool resource experiments to study individual and collective decisions around harvesting finite “common pool” resources. Participants in these experiments have been students and fishers from Sweden, Thailand and Colombia.

And better scientific understanding of decision making is not the only goal.

Yes. By running these behavioural experiments we also hope to create spaces together with participants to reflect and share experiences on what’s happening in their environments, how they relate and live with drastic changes and work collectively.

What do you enjoy most about your work?

I’m very curious about how we relate to our environments and how these relations shape us. I’m also very much motivated and inspired by working in an environment where collaboration underpins everything we do - something which is quite unique to the Stockholm Resilience Centre and its partner, the Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics, where I am based.

Given the systems we are dealing with are so complex, what insights are you able to provide when it comes to policy making?

It’s a challenge. To give specific policy recommendations we need context-specific information on the one hand, but also understanding of more general and fundamental processes on the other.

As complexity researchers we must determine what we are able to generalise and what we cannot. With their diverse perspectives, I’m really excited to explore this with all the other SRC researchers working on the interacting complexities theme.

This brings us nicely to the interacting complexities theme. Congratulations for being one of the three rising stars taking the helm! What are you most looking forward to?

First of all it’s incredibly exciting to be part of this new organisation of the centre’s work. There is a lot of new energy and enthusiasm that will generate lots of new ideas and collaborations.

Complexity perspectives are core to everyone’s work and I am looking forward to co-developing and nourishing a collaborative and inspiring space that allows us to engage more deeply with these perspectives, their applications and role in sustainability science.