Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

INTRODUCING OUR SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COUNCIL

From head to tone

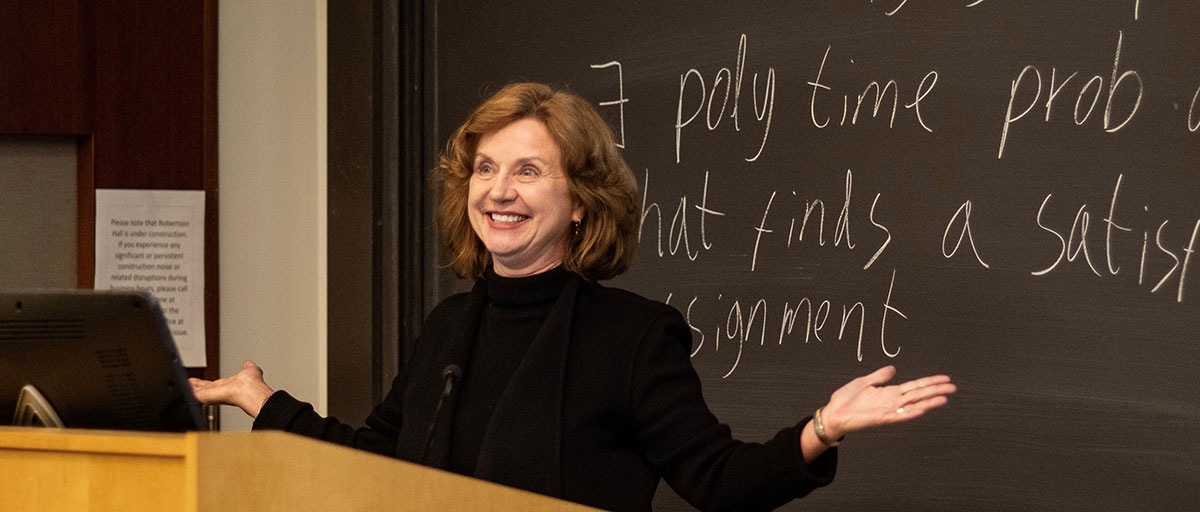

Elke Weber, a member of the centre's science advisory board, describes SRC’s research as “gutsy”, because it “cheerfully and successfully tries to do the impossible”. Photo: B. DeJesus/Princeton

- The International Scientific Advisory Council (ISAC) is a body of internationally leading researchers providing strategic advice and guidance on the scientific development and direction of the Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC)

- Elke Weber is a Princeton professor in psychology, public affairs, and energy and the environment

- She believes the centre’s first 13 years of existence have provided it with a solid foundation for future endeavours

Elke Weber, a Princeton professor and member of the centre’s science advisory board, knows a thing or two about the human brain and what it takes to get people to act

People are funny sometimes, but when it comes to dealing with environmental change they can be downright strange.

If we know our current treatment of the planet is leading us down a dangerous path, why don’t we do something about it, and fast?

An important place to start is in our own heads. For some that means removing them from a hole in the sand but for many it is about making better decisions. We like to think such decisions are rational and well thought through, but it is not always the case either.

Good thing then there are experts out there who can help us understand how our own minds and brains work. Because that might be where the real sustainability transformation will start.

Getting into the right set of mind

Elke Weber, a Princeton professor in psychology, public affairs, and energy and the environment, is certainly one of them.

Her research looks at the processes around decision-making and how humans motivate their actions. She then tries to use this knowledge to find ways to make better decisions.

The answer to that second part is, according to Weber, a combination of three things: how we frame messages (“hope and solutions always beats doom and gloom”), how we present options (“give people planet friendly options first”) and how we approach people’s struggle to deal with uncertainty, trade-offs or lack of action on issues where the results are not immediate or short-term (“ask people how they want to be remembered”).

All these aspects are crucial elements to help create sound and sustainable decisions for the future. And they are certainly valuable in the continuous development of sustainability science itself. Which is why Elke Weber’s acceptance to take on a role in the centre’s international science advisory board (ISAC) is much welcomed.

I am bringing my expertise in human decision processes to the SRC. That means the full range of cognitive processes and motivations that drive decisions in personal and professional decisions.

Trying to do the impossible

She describes SRC’s research as “gutsy”, because it “cheerfully and successfully tries to do the impossible”. That means bringing researchers from different disciplines and levels of seniority to generate high-impact research insights a variety of important questions.

These insights are then shared and applied with policy audiences and practitioners at different levels.

“The impressive final leg in this integration are the centre’s educational programmes that build capacity from undergraduate to executive level education,” she says.

Weber believes the centre’s first 13 years of existence have provided it with a solid foundation for future endeavours. This is good because there are plenty of challenges to deal with.

Online tools, “machine learning” and the use of artificial intelligence in data management will be important.

Technological advances and the information revolution have provided us with unmanageable amounts of data on almost every single facet of life. Now the machines that have helped generate this deluge will have to help us to turn this data into actionable information.

Need for new time horizon

Another challenge is our individual and collective time horizon, which currently is considered far too myopic.

Weber believes science has an important role to play in shifting people’s time perspectives. We need a longer time horizon, she says. Can science help with that?

“Social and behavioural science can help us devise ways that focus decision makers’ attention on the future by shaping the physical and social context in which they are made,” she says.

“Furthermore, the natural sciences and systems modelling can help us predict the negative consequences of procrastination and the positive impacts of a greater a greater focus.”

Time will tell how successful we will be.