Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

ONTOLOGIES

Why constant change is more important than stability

Researchers believe we must think of reality as something that is in constant change rather than being made up of objects that exist independent of each other. Like a forest which has been shaped by multiple social and ecological processes across time and space. Photo: T. Hertz

- Researchers argue for a way to close the gap between how we say we view social-ecological systems and how we treat them in research and practice

- They argue that we must think of reality as something that is constant change

- Such a shift in worldview would enable researchers to understand social-ecological systems in new ways

We talk and think in terms of things and entities that are stable and unchanging. This is understandable, but misguided, researchers argue

A FOREST IS MORE THAN JUST A FOREST: Research on social-ecological systems (SES) has highlighted their complex and adaptive character, but is something amiss in how we gather and apply knowledge about these systems?

Despite recognizing their dynamic characteristics researchers often base their analyses on parts of the systems that are isolated and static.

In a study published in People and Nature, centre researchers Tilman Hertz, Maria Mancilla Garcia and Maja Schlüter argue for a way to close the gap between how we say we view SES and how we treat them in research and practice.

Hertz explains “We talk and think in terms of things and entities that are stable, unchanging and have a defined set of properties. This is understandable, because doing so allows us to control, predict and manage our environment.”

However, he continues, this means that we might run the risk of neglecting what situatedness of people, as well as the social-ecological processes which influence who people are, or which processes people realize at any given moment.

People are not the same across contexts, nor do they behave the same. Hence, we need ways that allow us to account for the many processes and relations a person is embedded it.

Tilman Hertz, lead author

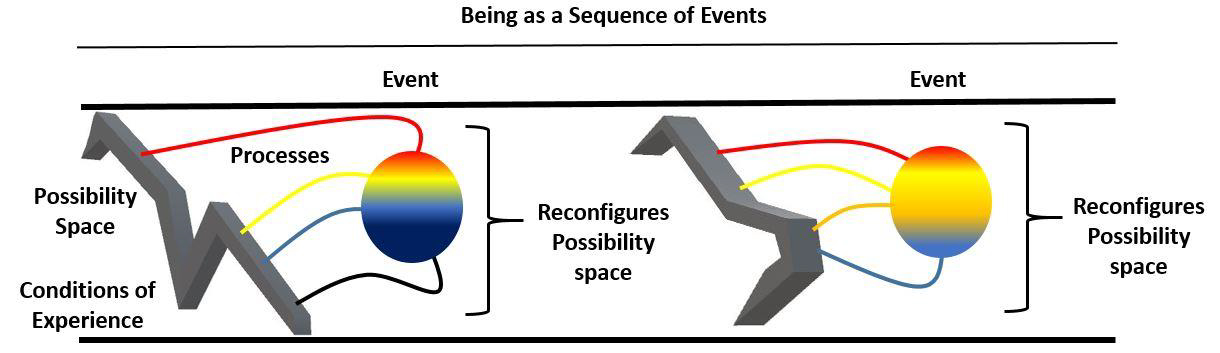

"Being" is understood as a sequence of events. Every event can be realized by many different processes coming from a variety of different realms such as the biological, ecological, social, cultural, or the aesthetic.

Assumptions have shaped percections

The authors reason that this mismatch stems from what in research is termed ontology – the way we describe things.

"Our paper presents an alternative philosophical perspective that allows us to see change as being more fundamental than stability," co-author Maja Schlüter adds.

The ontologies that underlie the tendency to divide SES into parts and describe them as sometimes stable entities have influenced most of contemporary science and are what is called “substance ontologies”.

They assume that reality is made up of objects that exist independent of each other.

Instead, the authors argue that we must think of reality as something that is in constant change.

Think of a typical forest. It changes all the time. You can see traces of how multiple social and ecological processes have shaped it over time and space: exploitation of wood, recreation areas, forest fires, seed dispersal, animal activities, cultural activities, beliefs or taboos. Together they create the forest we see and experience.

“Can we really understand what a forest is without taking into account how it is constantly shaped by past and present processes of interactions?,” asks co-author Maria Mancilla Garcia.

A shift in worldview

The authors believe “process ontologies”, which focus on concepts such as processes, events and possibilities would be more suitable for the study of SES.

They conclude that such a shift in worldview would enable researchers to understand SES in new ways and support the development of new governance approaches.

"This will enable SES researchers to conceptualize problems and help rethink policies from managing just people and instead managing relations between and among people and the natural system."

Hertz, T., Mancilla Garcia, M., Schlüter, M. 2020. From Nouns to Verbs: How Process Ontologies enhance our understanding of Social-Ecological Systems (SES) understood as Complex Adaptive Systems, People and Nature, doi:10.1002/pan3.10079

Tilman Hertz' research explores to what extent process ontologies can help us better understand social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems.

Maja Schlüter’s research focusses on analysing and explaining the co-evolutionary dynamics of social-ecological systems.