Researchers find that Fishery Improvement Projects have a tremendous potential if they confront some big weaknesses. One is skewed geographical focus. Most new initiatives have emerged in Asia, Central America and South America. Reporting and data collection must improve too. Photo: T. Castelazo/Wikimedia

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

FISHERY governance and sustainability

Going from promising to a source for good

New study provides first global analysis of private governance initiatives dealing with environmental challenges in fisheries. It shows how they come with tremendous potential but some big weaknesses too

- Fishery Improvement Projects (FIPs) are increasingly popular private sector led initiatives used to improve the sustainability of the global fishing industry

- In a first global analysis, centre researchers find that their potential can be fulfilled if new initiatives go beyond Asia, Central America and South America

- Reporting and data collection must improve too

Working with something that has potential can be both grateful and frustrating at the same time. That certainly applies for many sustainability initiatives where trade-offs are omnipresent.

Take Fishery Improvement Projects (FIPs) for example.

These private governance initiatives address environmental challenges in fisheries by connecting a variety of stakeholders who are well placed to develop and help implement new technologies or practices.

One example is the Gulf of California Industrial Shrimp fishery which struggled with compliance and regulatory enforcement. All FIP participating importers were asked to sign a control document, a verifiable mechanism for documentation of the supply chain. This helped the FIP to exclude vessels that were violating Mexican federal fishing regulations (e.g., fishing in restricted areas). The FIP also developed a third party audit system in which vessels under the control document were audited to ensure compliance with national regulations.

Despite an increasing popularity, from a handful in 2005 to 107 in 2015, FIPs have so far received little scholarly attention. The few studies that do exist focus primarily on what happens in the water and say little about how these initiatives actually work.

Said and done, in a recent study in PLOS ONE, centre researchers perform the first ever global systematic analysis of the actions undertaken within FIPs to promote fisheries sustainability, linking them to the actors involved in each action, in different parts of the world, and across different fishery types.

Improve, but confront some big weakness first

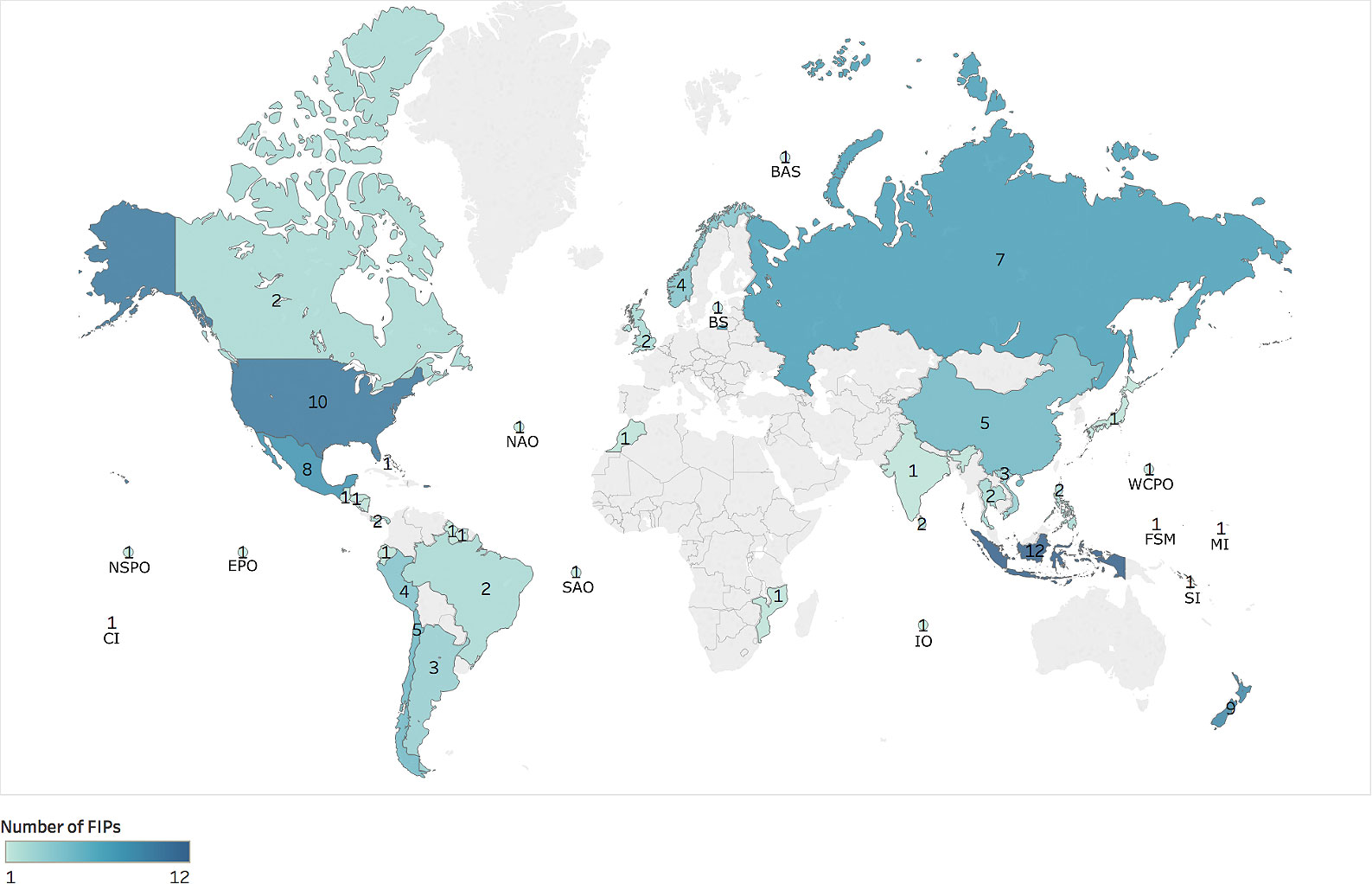

The authors argue that FIPs have a tremendous potential if they confront some big weaknesses. One is skewed geographical focus. Most new initiatives have emerged in Asia, Central America and South America where the retail sector has a strong influence on sustainable seafood production.

Big retailers tend to be interested in species that are traded at a global scale, and can be sourced in large homogenous volumes, such as whitefish, shrimp, crab and lobster. This may explain why we see much fewer FIPs in Africa and the Pacific.

Beatrice Crona, lead author

Another weakness is inconsistent reporting. Current procedures are not standardized which stops researchers from producing any kind of general insights that could help them get better.

“This will limit our understanding of how FIPs operate and hamper learning that could otherwise improve the FIP governance process and be capitalized on by future FIPs,” co-author Tracy Van Holt explains.

Data collection and inconsistent strategies

Then there is data collection. FIPs can be found across many different fisheries such as tuna, shrimp, whitefish, crab and lobster industries. While they are diverse in character, a common action undertaken across almost all types of fisheries is data collection. This is not surprising, given its importance for justifying the initiation of many FIPs. It is also a key priority for the Marine Stewardship Council’s benchmarking process which many FIPs follow.

What is surprising, however, is that data collection is primarily focused on biological data rather than on fishers’ behaviour. This prevents researchers from studying behavioural changes over time – arguably of key importance to any initiative hoping to make fisheries more sustainable.

There are also several other strategic inconsistencies among the FIPs. Some are designed to either engage with policy, or to change practices but rarely both. Crab and lobster FIPs report deeper policy engagement, while shrimp and tuna FIPs generally report stronger engagement with practice.

An example of policy engagement is the blue swimming crab FIPs in Southeast Asia, where the industry is working closely with governments to develop guidelines for best practices and improved regulations.

“Indonesian government officials have even travelled to the US to meet with the National Fisheries Institute Crab Council to learn more about fishery management,” notes Sofia Käll, co-author of the study.

“The stronger engagement around practice across tuna FIPs in particularly may result from the fact that governance discussions of tuna often take place at the level of regional fisheries management organizations - which are often not accessible to FIP actors – and therefore engagement with policy actors is less accessible to tune FIPs”, she explains.

As a conclusion, the authors believe FIPs can play an important role to support fisheries sustainability. To do so however, they need to deal with the listed in their study. If they do, FIPs can turn their potential into a force for good.

Worldwide distribution of Fishery Improvement Projects (FIPs) in 2015.Numbers within countries represent the number of FIPs per country. Numbers in oceans represent the region of multinational FIPs. Letters represent the names of ocean regions or islands nations. Darker colors of countries indicate larger number of FIPs. (BAS: Barents Sea; BS: Baltic Sea; CI = Cook Islands; EPO: Eastern Pacific Ocean; FSM: Federated States of Micronesia; IO: Indian Ocean; MI: Marshall Islands; NAO: North Atlantic Ocean; NSPO: North South Pacific Ocean; SAO: South Atlantic Ocean; SI: Solomon Islands; WCPO: Western Central Pacific Ocean). Figure made using Tableau Software. Click on illustration to access scientific article.

Methodology

Publically available progress reports constituted the raw data and the analysis was conducted in three steps: 1) compilation of a database of all, in 2016, known FIPs, 2) drafting of a set of criteria to evaluate the quality and assessability of the progress reports, and 3) iterative development of a coding framework to analyse actions, actors, and outcomes. The sample of FIPs and the codebook allowed for analysis across geographical places and fishery types. It is noteworthy that 56 out of the 107 FIPs were not assessable due to insufficient data or inactivity. At the time of data collection there were no standardized reporting requirements pertaining to FIPs, something that proved comparison challenging. However, since 2016, www.fisheryprogress.org has been established and serves as a one-stop source for information on FIPs.

Crona B., Käll S., Van Holt T. 2019. Fishery Improvement Projects as a governance tool for fisheries sustainability: A global comparative analysis. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0223054