In an experiment on fishing behaviour and market prices involving several hundred fisherwomen and fishermen in the Philippine province of Iloilo, gender roles were found to be a stronger predictor than price. Photo: J. Flores/Team Gorgeous

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Global trade and fisher behaviour

Gen(d)erating local responses to global market signals

In Philippine fishing communities, gender roles have a bigger influence than price on fishers’ business decisions

- 251 Philippine fisherwomen and fishermen participated in a behavioural economic experiment exploring the link between global market price and fishing behaviour

- Gender roles were found to be a stronger predictor than price. Fishers’ will and capacity to change business strategies are also largely determined by local informal structures of financing

- Behavioural economic experiments move beyond rational decisions understood as strictly economic and also account for contextual factors

What would you do if you were offered a higher price for something that you are selling? Your first instinct might be the rational economic response: produce more, sell more, and laugh all the way to the bank. But then you give it some more thought and realize that many factors will affect your decision. What financial risks are involved? How much additional time do you have, do you actually need more income? Is going ‘big’ always the most desirable way forward?

The answer is not that straight forward. According to a new study published in Frontiers in Marine Science, in Philippine fishing communities, the decision may depend on your gender.

There is a lot on a rational mind

Small-scale fisheries (SSF) are increasingly connected to global seafood markets through export. Fishers receive a price set by international markets and it is unknown how this impacts their fishing activities and subsequent local human and ecological wellbeing.

In a behavioural economic experiment with Philippine fishers, centre researchers lead by Elizabeth Drury O’Neill explored how fluctuating world market prices influence fishing behaviour. Suspecting that fishing decisions are more than a mere balance-sheet exercise, they tested the influence of price under variable fish stocks, while controlling for social and cultural factors.

Much SSF research and fishery improvement projects rest on assumptions of rationality although these assumptions are unlikely to hold true in the context of small-scale societies. Our approach may better inform attempts to develop sustainable fishery interventions.

Elizabeth Dury O’Neill, lead-author

Custom-made design

In many tropical SSF communities, patron-client relationships replace formal financial infrastructures. Patrons finance fishing operations by providing loans in exchange for supply and loyalty. It is common that patrons also trade the catch; it is ultimately the patrons that pass on information about market prices to fishers.

Patron-client relationships, or suki, are a key feature in the Philippine province of Iloilo. The most common loans are for fuel and fishers participating in the experiment were asked to make decisions about how much fuel to borrow from a patron in light of changing market prices and variable fish stocks. Price symbolized a new connection to an international market while size of fuel loan implied the predicted fishing effort. Fishers made a profit based on fuel costs and catches.

In addition, the researchers wanted to know which household and individual characteristics influence fuel loan decisions. Through interviews and observational data, they collected information on the participants’ gender, suki-arrangements, economic situation, financial risk preference, and fishing gear.

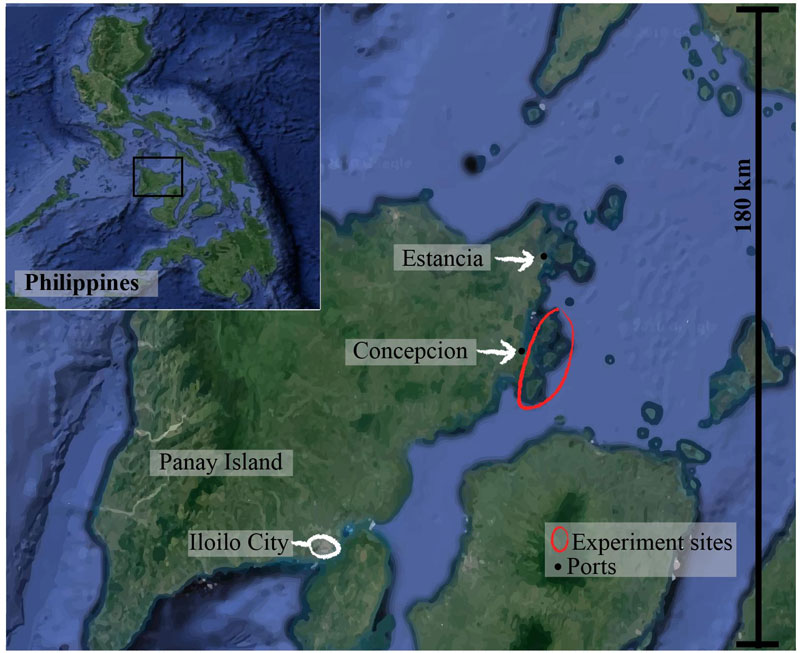

Location of field study: Panay island location in Philippines (inset). The Capital of the main province on Panay Island, Iloilo, can be seen circled in white to the south- Iloilo City. Concepcion is located on the North Eastern seaboard as is Estancia- the other major, and larger fishing port and town to the North of it. The area where the experimental sites are is circled in red.

‘Big Big Big’ rational men

Contra to the researchers’ expectations, fishers showed no response to an increase in price. Nor were larger loans taken by risk-seeking fishers, fishers with larger vessels, or with stronger suki-relationships. Neither did the level of household savings play any role. Instead, fuel loan decisions turned out to be a question about gender. The fisherwomen chose smaller loans 78 percent of the time compared to 54 percent among the fishermen. Many fishermen took large loans in the first rounds and kept on playing it ´big´ throughout the experiment.

The researchers did not find any gendered differences in terms of individual or household characteristics. Puzzled, they dug deeper. Through the interviews, they discovered that there are strong gender roles at play in Philippine fishing communities.

“Men are expected to do longer and more dangerous fishing trips while women split their time between ´lighter´ sea work and the household. To opt for bigger loans and bigger catches in the experiment might have been a way for the fishermen to prove their masculinity”, explains co-author Therese Lindahl.

Context, context, context

The results emphasise the importance of the social, cultural, and economic context of fishers.

“Changes in the global market are not immediately observable on the local level as the fishers’ capacity to respond is determined by local conditions” says Drury O’Neill.

Sometimes fishers lack the technical and financial capacity to change strategy and sometimes the price just does not matter. Participants indicated that it is unusual to shop for the best catch price among patrons.

The patron-client relationships vary in form and strength; they can be financial arrangements only or longstanding personal relationships. They can be inflexible and unfavourable or really happy with loans never being fully paid back to ensure that the relationship continues. 77 percent of the participants stated that they prefer the suki-system over bank loans and other formal (and impersonal!) arrangements.

For research and governance projects alike, the lesson is that reducing market dynamics to price, catch, and demand will only tell you so much about what is happening on the ground. Or at sea for that matter.

Methodology

251 fishers from the municipality of Concepcion in the Iloilo province partook in the behavioural economic experiment. 11 sitios (Island settlements) across 4 island barangays (smallest administrative unit in the Philippines) were sampled. 22.7 percent of the participants were women, a figure that seems representative for the fishing gender ratio in the area.

For 12 rounds, fishers were informed of the fish prices and asked to make a decision to take a big or small fuel loan from a patron or no loan at all and refrain from fishing. The participants were divided into three treatment groups who experienced 1) no price changes, 2) a price increase in round 4 for those taking a big loan, and 3) a price increase in round 4 and a decrease in round 8. Catches were drawn randomly and distributed according to loan size with larger catches only possible for bigger loans.

All loans were paid back at the end of each round from the sale of the catch and cumulative income was recorded and shared with the fishers. Interviews, focus group discussions, and observational data provided both background information to validate the design of the study and helped contextualize and interpret observed behaviour. Statistical analysis was applied to the experimental data and data on individual and household characteristics to assess correlation.

Drury O’Neill, E., Lindahl, T., Daw, T., Crona, B. et.al. (2019). An Experimental Approach to Exploring Market Responses in Small-Scale Fishing Communities. Frontier in Marine Science.

Tim Daw studies the interaction between ecological and social aspects of coastal systems and how these contribute to human wellbeing and development