New study explores how patron-client relations in the Philippines buffer against natural disasters in the short term, at the potential cost of long-term sustainability of coastal livelihoods. Photo: E. Drury O'Neill

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Small-Scale Fisheries

Float a loan to weather the storm

Patron-client relations in the Philippines buffer fisheries against immediate impacts of natural disasters. But long-term sustainability may suffer due to the combination with current fishery conditions

- Patron-client relations buffer fisheries against immediate impacts of typhoons and filter aid interventions

- This can have negative consequences for the long-term sustainability of livelihoods and the marine ecosystem due to the current system state i.e. lack of fishery enforcement and high economic vulnerability

- A systems approach draws out the historical development of the fishery after the system shock, unpacking short- and long-term impacts for the social and ecological.

Acts of good will and reciprocity lay the foundations that can strengthen bonds within societies. When you’re a fisher on the coastline of the Visayan sea in the Philippines, that gets hit by 20 typhoons a year, you’ll want the strongest foundations you can get.

In November 2013 one of the most powerful Super Typhoons on record hit the Philippines. It went by the name of Yolanda, and left a path of destruction in its wake, ripping up the fragile coral reef, tearing apart homes and taking lives.

The work of centre researchers Liz Drury O'Neill and Beatrice Crona, recently published in Environmental Research Letters, draws upon data collected in the years following Yolanda, when the effects could still be seen. They look at how loans through reciprocal arrangements, known as patron-client relations, can help buffer the disturbances caused by the typhoon and resulting aid interventions.

The study brings into question how these relationships play out in the long term when looking at the larger fishery system.

Increased individual-level resilience may come at the expense of longer-term fishery system sustainability, by promoting unsustainable behaviour that undermines the marine ecosystem upon which people depend.

Elizabeth Drury O’Neill, lead author

Buffering the costs

In the Philippines patron-client relations are known as the ‘suki’ system. The brokers at the ports (that trade fish to big cities, such as Manilla) and buyers in the local villages act as patrons, fishers their clients. They know that if they lend a helping hand, fishers will return the favour when their fish harvest comes. After Yolanda, the fishers used cash advances to repair damaged boats, fishing gear or for fuel to move to fishing zones that had been less damaged by Yolanda. Brokers and buyers too used loans from their own patrons to supply this cash to fishers. However, years on from Yolanda many loans remain unpaid leaving fishers stuck in big debts and patrons out of pocket.

Describing patron-client relationships in general. “They are usually voluntary, asymmetrical in terms of power, mutually beneficial, and often marked by an affinity between the patron and client through ethnicity or religion or some shared experience, like a common threat.”

Unintended consequences of aid interventions As the ebb and flow of the tide brings changes, the ebb and flow of typhoons brings much bigger changes. Drury O’Neill explains: “Coastal communities are familiar with the crises caused by typhoons and the cycles of rebuilding and recovery of houses and livelihoods which are habitually repeated.”

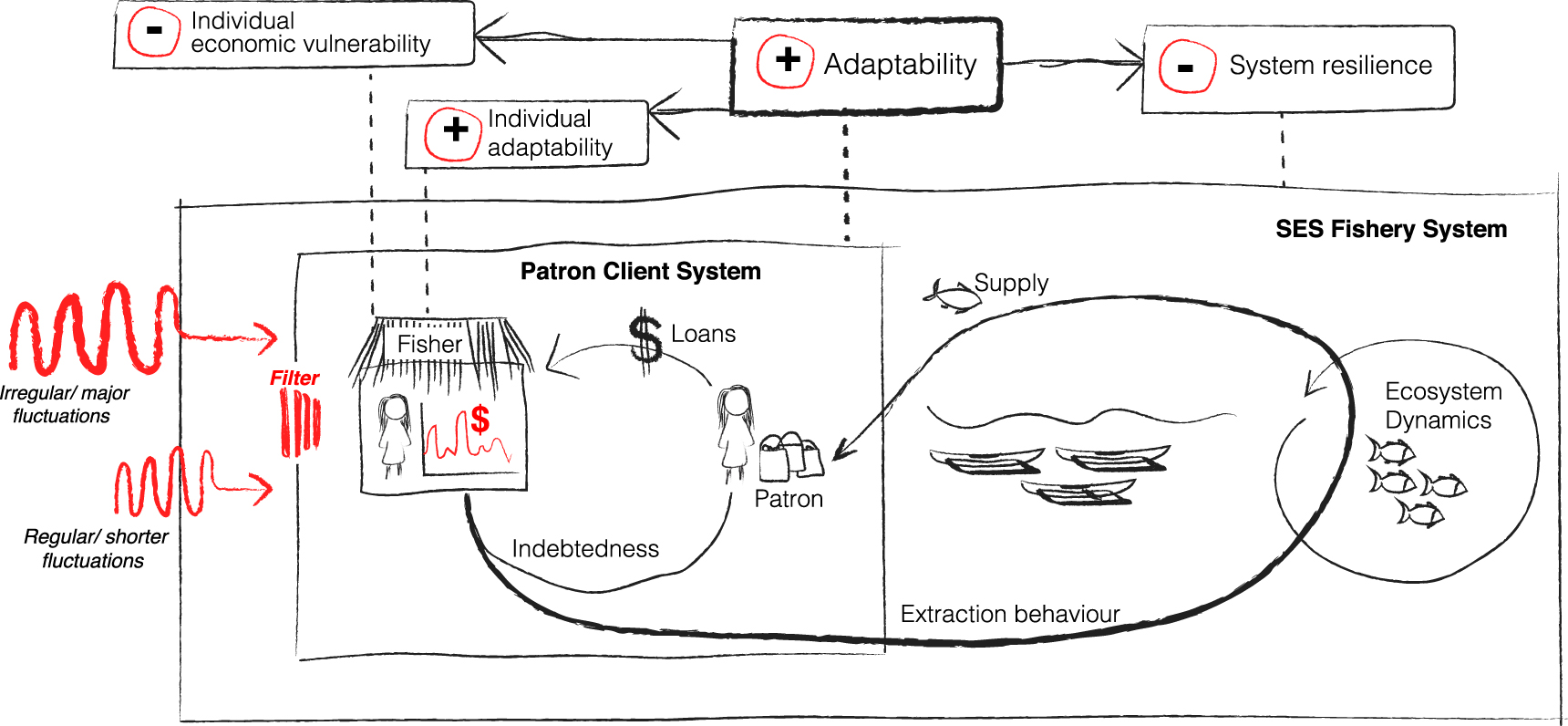

Conceptualization of a fishery system with fishing households (the little house on the left of the figure) facing regular, short-term disturbances, i.e. daily price and catch fluctuations, and larger, more infrequent shocks, such as management interventions, global markets, aid and typhoons. Click on illustration to access study

Aid not evenly distributed

But the damage caused by super typhoon Yolanda was beyond what many had experienced. Aid interventions flooded different communities, from banks, NGOs and philanthropic donations. However, it was not evenly distributed, with some districts receiving more than others. The unintended consequences of this aid unraveled in the years following the typhoon.

A fishery official explains the nature of the problem: “We can’t control the NGOs giving out boats, they gave boats to crew members and even some people got two boats. Now there is increased competition among the fishers, there are more little boats. Before there were bigger boats with bigger catch.”

Giving out small boats was a strategy that NGOs and provincial government devised together- seeing this disaster as an opportunity to remove the pressure of larger commercial vessels by not replacing them. But this homogenisation of the fishing fleet signals increasing pressure in coastal waters as smaller boats are confined to certain grounds due to size and fuel capacities.

As so many boats were donated, some people felt encouraged to enter the fishery as patron traders to support the increased fishing units. Older patrons felt the need to continuously give loans to keep good relations with current clients for fear that they might find new patrons in this seemingly booming market. The majority of the aid, although well intended, did little to rebuild the long-term damage done.

Taking a systems approach

The Visayan sea’s biological health is worsening. There are fewer fish and the species are changing, according to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. Understanding the interconnections of this system is vital to improving the implementation of aid interventions. The authors mapped the insights gathered from many actors in this system to describe the causal pathways that can be triggered by different impacts, such as local natural disasters and global markets (Figure from paper).

Social indebtedness tightens bonds and can bring fishers, brokers and buyers closer together. It can also sustain fishing pressure due to the need to pay back loans through fishing and bring a lack of economic security for households that become over-reliant on loans. These latter effects are what the authors conclude are detrimental to the long-term sustainability of the fishery.

“Given the forecasted increase in climate driven extreme weather events, understanding how patron-client relations mediate local system responses to highly disruptive, natural shocks, and the aid interventions that often come in their wake, is essential.”

Methodology

Research took a case study approach of small-scale fisheries systems within the Iloilo province, Philippines. Insights of the system dynamics were gained through key informant interviews, participant observations, structured interviews and focus group discussions with fisherfolk, traders, NGO representatives and municipal and provincial level government officials. They also looked at official reports of post-Yolanda events. As well as interactions in fisher-broker/buyer relationships, the researchers also looked at patron-client relationships between trading agents. All these datasets were brought together with process tracing methods to analyse the causes of the current circumstances.

Drury O'Neill, E., Crona, B., Ferrer, A.,J.G., Pomeroy, R. 2019. From typhoons to traders: the role of patron-client relations in mediating fishery responses to natural disasters. Environmental Research Letters, Volume 14, Number 4

Elisabeth Drury O’Neill is a postdoctoral researcher focusing on coastal livelihoods, fisheries and marine resource governance.

Beatrice Crona’s work centers on various aspects of oceans and fisheries governance, as well as understanding different emerging global connectivities and their effects on social-ecological outcomes at multiple scales.