In a study recently published in the journal Fish and Fisheries, researchers has applied scenario training to develop narratives on how the Barents Sea might look like in 2050. However, they developed their own method which flips conventional scenario development on its head. Instead of asking participants to create narratives together, they asked them to present their own individual perspectives about the future state of the Barents first. Photo: M. Dawncat/Flickr

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

SCENARIO DEVELOPMENT

The sum of single perspectives

New method flips conventional methods on scenarios on its head, creating narratives based on a variety of single, often conflicting perspectives. That generates a more realistic understanding of a complex world

- Researchers applied scenario training to develop narratives on how the Barents Sea might look like in 2050

- Instead of asking participants to jointly create a narrative, the researchers asked them to present their own individual perspectives about the future state of the Barents Sea

- The method makes it easier for each participant to enter the exercise with some idea about the future, and exit with a better understanding of the complexity of the situation, the associated uncertainties and other actors’ point of view

Thinking about the future is an important part of our need to organise our lives, no matter how uncontrollable the future inevitably is. It is also a personal thing, we do it in our own way, based on our own needs. But anticipating changes to our global environment and collective future is indeed the concern of many of us. That goes for our oceans as well.

In a study recently published in the journal Fish and Fisheries, centre researcher Susa Niiranen together with colleagues from Norway and France has applied scenario training to develop narratives on how the Barents Sea might look like in 2050. The study was initiated and led by Benjamin Planque (nstitute of Marine Research, Norway) and Christian Moullon (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Université Montpellier).

The researchers developed their own method which flips conventional scenario development on its head. Instead of asking participants to create narratives together, they asked them to present their own individual perspectives about the future state of the Barents first.

These perspectives, several of them revealing contrasting priorities, needs and interests, where then integrated into three general scenarios about the Barents Sea.

Three narratives based on contrasting priorities, needs and interests

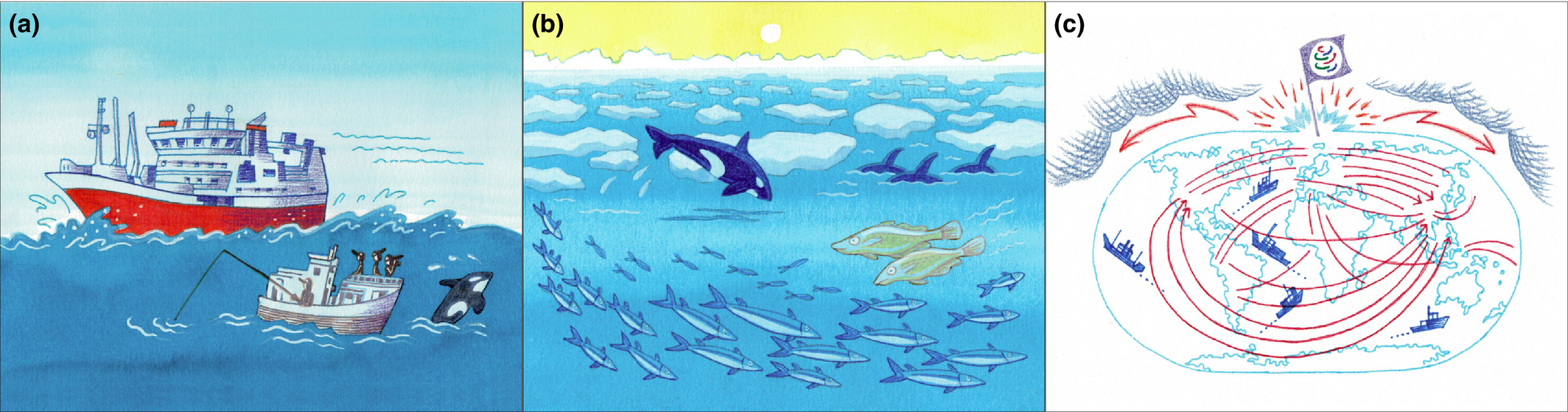

Scenario A described a 'baseline' future where a small number of fishing companies dominate the industry. Sea water temperature is rising and ice cover decreasing, yet the Barents Sea ecosystem is healthy and fisheries are productive. The global economic situation remains strong.

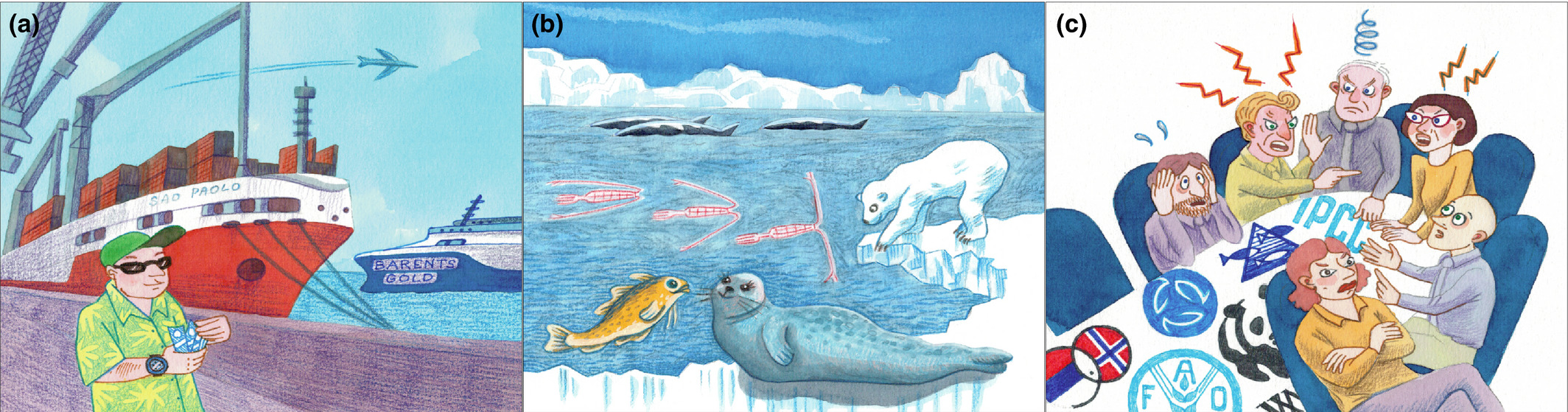

Scenario B described a future with cold climate and healthy ecosystem despite decline in global governance and fisheries management resulting from declining, trust between scientists, fishing companies and managers. The production of fisheries resources remains largely as today, but the economic value of them increase due to high demand in combination to degradation of many other fishing grounds. The return of colder climate has led to the resurgence of previously endangered or declining species such as polar bears and seals.

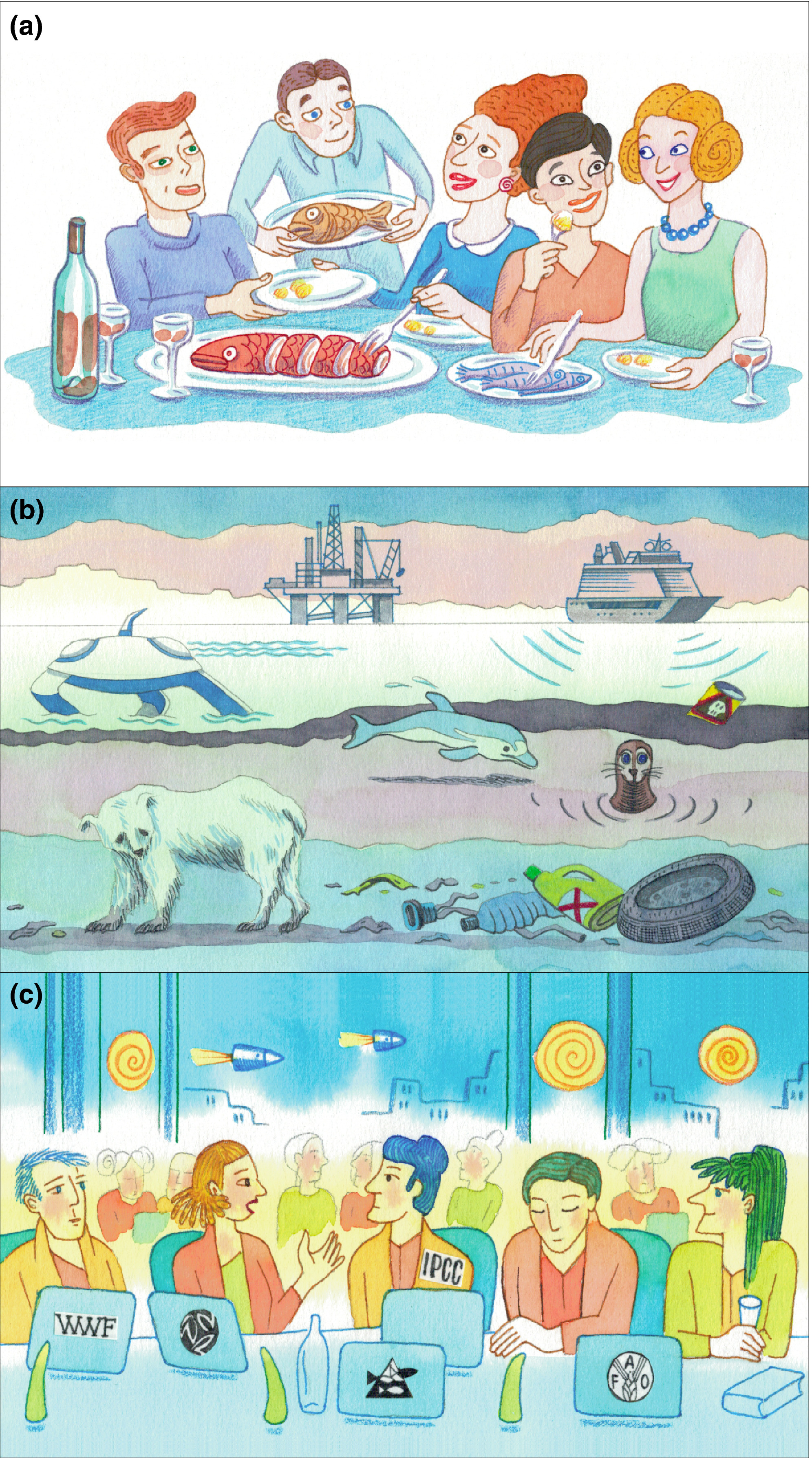

Scenario C described a future where no large-scale changes take place in climate nor global governance. Despite improvements in fisheries management, the ecosystem health is worsened and fisheries productivity has decreased making the Barents Sea a well-managed, poor health system. Simultaneously, the demand for international seafood is growing together with shipping, Arctic tourism and oil exploitation that increase pollution, microplastics and oil residues.

Several interesting new insights

Based on the exercise, Niiranen and her colleagues could draw a series of conclusions:

First of all, the use of scenarios is not sufficiently developed within marine research and management. Many of the participants had not worked with scenario methods before and knew little about how they worked. As a result, a significant effort was required to inform, educate and justify the reasons for using scenarios.

“It proved important to emphasize that being prepared for the future does not entail a capacity to predict the future, but rather the ability to set oneself in a situation that is sufficiently plausible,” Niiranen explains.

Secondly, asking the participants to start with their own single-perspective storylines before creating more integrated scenarios made it easier for them to get started. “It takes into account that all actors start from their own experiences and anticipations,” Niiranen explains. Asking the participants to first focus on the creation of joint scenarios was time consuming and difficult without a sufficient level of preparation, engagement and trust. It was also important to stress that all the individual perspectives were equally important.

Thirdly, sett the time horizon to 2050 made it easier for the participants to avoid being tangled up in personal accountability issues. Another insight from the workshop was that identifying and acknowledging uncertainty and even unlikely events is important. The last point can be illustrated with the following anecdote from the workshop: At the time of the meeting, in June 2016, there was much discussion around the chances of Brexit and Donald Trump becoming president. No one in the group believed any of the events would happen. History proved differently. This, Niiranen says, underlines the importance of ignoring so-called “wildcards”, because they have the potential to change political, diplomatical, legal and commercial global interactions.

Going in with single perspectives in, going out with a complex understanding

Based on all this, Niiranen stresses the importance of keeping things simple. “Keeping a level of simplicity in the scenarios and writing them in a language easily understood by everybody involved was important,” she says. The three final scenarios were eventually presented in the form of cartoons which helped clarify the messages (see above).

Niiranen and her colleagues are careful not to present this scenario method as a way to predict the future but rather to help manage it. “There is often confusion between scenario and prediction, between anticipation and management. This scenario building exercise is about helping confront the concerns and different points of view different stakeholders might have about the future of a marine social-ecological system.”

They conclude: “We propose a method where each actor who enters the exercise with some idea about the future, can exit the exercise with a better understanding of the complexity of the situation, the associated uncertainties and other actors’ point of view.”

Planque B., Mullon C., Arneberg P., et al. 2019. A participatory scenario method to explore the future of marine social‐ecological systems. Fish Fish. 2019;00:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12356

Susa Niiranen’s research focuses on change in marine ecosystems that is driven by multiple environmental and anthropogenic stressors