Biodiversity offsets are increasingly promoted as a way to compensate for biodiversity losses caused by infrastructure development projects. Critics argue this is putting a price tag on nature but most biodiversity offset policies are far from being “free markets”, according to a new study. Photo: F. Werneck/Ibama Wikimedia Commons

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

OFFSET POLICIES

No market without the state

Despite a variety of designs, the state plays a key role in all forms of policies around biodiversity offsetting

- Critics of biodiversity offset policies have pointed to the argument of putting a price tag on nature, thus turning it into a commodity

- But biodiversity offsets are more diverse than just “markets for ecosystem services”

- None of the assessed biodiversity offset policies in the study are close to “free markets”. The more a design likens a free market, the more government capacity is needed for monitoring and enforcement

Biodiversity offsets, or BO, are increasingly promoted by governments and companies as a way to compensate for biodiversity losses caused by infrastructure development projects. Based on the developer-pays-principle, BO requires those who exploit natural resources to fund the costs of environmental protection or restoration activities somewhere else. Critics have pointed to the argument of putting a price tag on nature, thus turning it into a commodity. BO and other kinds of offsetting schemes contribute to this perception.

Is a clarification in order?

Defining the role of the state

In a study recently published in Journal of Environmental Management, centre PhD student Niak Sian Koh along with colleagues Thomas Hahn and Wijnand Boonstra provide an overview of six different versions of a BO policy.

Their conclusion is that the characterisation of all BO policies as ‘markets for ecosystem services’ is a misrepresentation. In fact, the state plays a key role in all offset policies.

The state plays a key role, whether it is matching the biodiversity loss with gains, setting up trading rules or granting legitimacy to the compensation location

Niak Sian Koh, lead author

This means that governments considering adopting such biodiversity policies can design them with a high or low market involvement to match its own “political-economic culture”.

To better define the role of the state, Koh and her colleagues identified three ways a BO policy is realised: Public Agency, Mandatory Market, and Voluntary Offset. In the first, the state makes the decisions on the biodiversity valuation and transaction. This means they also plan, conduct and monitor the compensation project. In the second, the market enjoys a bigger freedom to decide which banks to use and what landowners to approach. The price of the compensation is also decided by market forces, as opposed to state estimates. In the third case, there is neither of the above, but compensation rests on the developer’s own sense of responsibility. This enables companies to set precedence where BO policies are still not established and influence any emerging legislation. Voluntary offsets are mostly done by extractive industries operating in the global South.

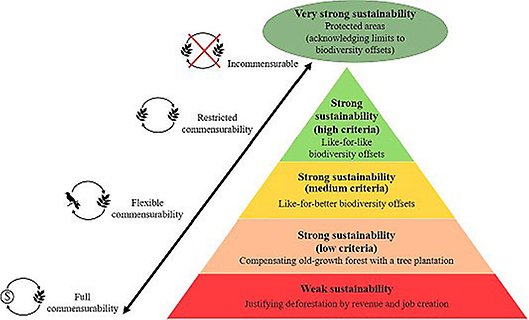

The spectrum of commensurability of nature, with four modes corresponding to strengths of sustainability. Click on illustration to access article

Six case studies

Guided by these characteristics, the researchers examined six policies from six equally diverse political, economic and geographical contexts:

1. The U.S. Wetland Mitigation Banking, which aims to achieve No Net Loss of wetland acreage and function

2. Biodiversity offsets in New South Wales, designed to address the clearing of native vegetation for urban development

3. German compensation pools and eco-accounts, all part of a deregulated national compensation policy to manage development effects on land use change and ecosystem functions, except for the impacts of agriculture, forestry and fishing

4. The British Biodiversity Offsetting pilots designed to achieve ‘No net loss of priority habitats’ in the country

5. Biodiversity offsets in the Western Cape province in South Africa, introduced as a way to finance protection of threatened habitats. The focus is therefore to avert loss rather than restore biodiversity

6. Offset policies introduced by Rio Tinto Madagascar Minerals, a British-Australian-Malagasy mining company. The goal is to achieve a ‘Net Gain of littoral forest and high priority species by 2065’, which is the anticipated date of mine closure.

Niak Sian Koh and her colleagues conclude that the six cases all have a strong element of state intervention in them. For instance, the Malagasy government has been involved in locating offset sites for Rio Tinto Madagascar Minerals. Similarly, German municipalities identify suitable sites of ecological value and gather them for creating a compensation pool, while the South African National Biodiversity Institute identifies priority conservation areas in the Western Cape Province.

The more of a free market, the more government is needed

“We find that none of the assessed BO policies are close to “free markets”, co-author Thomas Hahn explains. One reason for this is because monitoring and enforcement is both desired and expected.

"The more a design likens a free market, the more government capacity is needed for monitoring and enforcement."

“Our results suggest that even biodiversity offset policies that are often characterized typical markets for ecosystem services are in fact very far from standard markets,” third author Wijnand Boonstra adds.

This is because biodiversity offsets are based on strong sustainability criterion and strict guidelines about how to match losses and gains in biodiversity. Instead, a diversity of policies exists, from strongly restricted markets to government-led liability procedures with no market aspects and purely voluntary offset policies. But the state plays a key role in all of them, the authors conclude.

Methodology

To provide a framing for understanding the empirical diversity of BO policy designs, the researchers developed an ideal-typical typology based on the institutions from which BO is organised: Public Agency, Mandatory Market and Voluntary Offset. With cross-case comparison and stakeholder mapping, they identified the institutional arrangements of six BO policies to analyse how the biodiversity losses and gains are decided. The decision-making process of each policy is described in a stepwise order. Based on these results, they examined how these six policies relate to the BO ideal types.

Koh, S., N., Hahn, T., Boonstra, W.J. 2019. How much of a market is involved in a biodiversity offset? A typology of biodiversity offset policies. Journal of Environmental Management Volume 232, 15 February 2019, Pages 679-691

Niak Sian Koh is a PhD candidate researching policy tools for balancing development with the conservation of biodiversity and social equity.

Thomas Hahn’s research focuses on ecological and institutional economics in relation to ecosystem services, financial instruments, and adaptive governance of social-ecological systems.

Wijnand Boonstra's research investigates the social-historical dynamics of primary resources, and how it impacts the long-term biocultural sustainability of sea- and landscapes.