Participants of a land management workshop in a smallholder village in Drakenberg. A new study shows how historical discrimination laws, and, limited access to land and natural, financial and technical resources leave smallholder communities trapped in poverty. Photo: R. H. Malinga

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Inequity and access to ecosystem services

On the other side of the ditch

Study reveals deeply contrasting realities for farmers in South Africa

• Smallholder farmers at the foothills of the Drakensberg mountain range live right next to commercial farmers with large land holdings

• Vast inequities originating from historical discrimination laws, and, limited access to land and natural, financial and technical resources leave smallholder communities trapped in poverty

• A combination of land reform, financial support and increased skills on how to develop sustainable, multifunctional agriculture is needed, but implementation of various strategies is hard

Social inequities manifest themselves in many ways in South Africa. At the foothills of the Drakensberg mountain range, the contrasts are stark. Separated only by a 2 kilometres long ditch, life is very different depending on what side you live on.

On one side, a 56 year-old grandmother of 12 owns eight cattle and four goats that graze in the communal grasslands during the summer. She also grows maize and beans on two hectares crop fields. The grandmother is the main worker on the field, occasionally assisted by other members of the family when they are available. From her own fields she can look over to her neighbour’s 1200 hectares farm with large, irrigated crop fields and grazing land holding 260 sheep and 740 cows. The neighbour, a 38 year-old father of three, inherited the farm from his own father and has since then extended it by 500 hectares of grazing land.

Population groups in South African with ethnicities other than whites with European origin have historically been denied the opportunity to own land. The legacies of this discrimination persists today through unequal access to land, education and development opportunities. That remains very much the case for the farmers in Drakensberg too.

Embedded in the landscape are vast inequities originating from historical discrimination laws, and, because of their lack of access to land and natural, financial and technical resources, smallholder communities risk remaining trapped in poverty.

Rebecka Henriksson Malinga, lead author

Same services, different benefits

Despite living off the same land, the agricultural landscapes these two neighbours manage are rich in contrasts. They also represent two distinctly different land tenure systems: communal villages under traditional tenure rules and privately owned land with exclusive access.

In a study recently published in Ecology & Society, Rebecka Henriksson Malinga, a former centre PhD student, now a postdoctoral researcher at University of KwaZulu-Natal, together with centre researchers Erik Andersson, Line Gordon and others, studied the distinctly different lives of farmers living in Drakensberg.

Specifically, they studied 20 farms in the upper part of the Thukela River catchment trying to understand how they benefit from various ecosystem services such as crop production, firewood, recreation, and access to water. Ten of the farmers in the study where male commercial farmers and the other part consisted of five female and five male smallholder farmers from two traditional Zulu villages.

Link to publication

Request publication

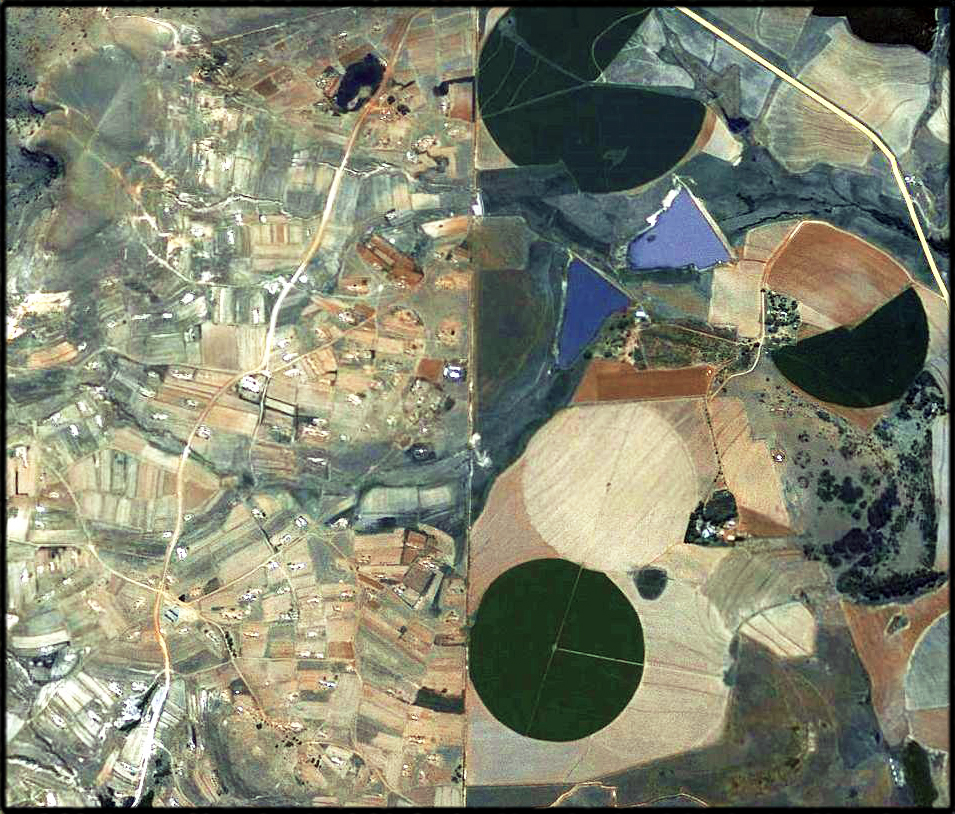

Satellite image of the ditch separating one smallholder village and one commercial farm. Photo: Google Earth (2009)

In their study, Henriksson Malinga and her colleagues conducted a mapping exercise to capture the farmers’ supply (use and perception) of, and demand for, 16 selected ecosystem services. Perhaps not surprising, the smallholder farmers provided considerably different perspectives from their more affluent neighbours.

The differences were especially large in terms of crop and livestock. Commercial farmers had on average six times higher agricultural production and much higher supply of soil and water-related ecosystem services than the smallholder farmers. The supply of ecosystem services through commercial agriculture was enough to maintain a lifestyle that they had chosen, primarily through the income generated from the farming. Smallholder farmers, on the other hand, use their lands largely for feeding their families. Their demand was higher than the supply meaning that additional food has to be bought elsewhere.

Different attachment to the landscape

Another interesting difference was their valuation of cultural heritage. Commercial farmers mentioned cultural-historic heritage mainly in the form of remnants from previous people, such as rock paintings, stone kraal ruins, historical mining sites and fossils.

Their attachment to them was rather low, as described by one of the commercial farmers:

“There are some hundred year old stone house ruins and ancient stone kraal ruins on my farm, but if I need the stones or if they are in my way I will remove them. They are not valuable to me.”

Smallholder farmers, on the other hand, actively use their landscape for carrying out cultural ceremonies and rituals.

Traps and environmental implications

Overall, the study revealed considerable differences between the landscapes, both in terms of supply of services and how they met farmers’ demand for services.

“For most of the ecosystem services we assessed, commercial farmers had a high capacity to influence the supply of services and to meet their demand. Smallholder farmers, meanwhile, struggled,” Rebecka Henriksson Malinga explains.

These social and economic differences have environmental implications too. While both the smallholder and commercial landscapes can be seen as multifunctional by meeting environmental, social and economic needs of society to some degree, both landscape types require changes to increase multifunctionality and sustainability.

On one hand, commercial farmers have some strategies in place to improve grassland health, soil quality and reduce soil loss, but on the other hand they perceive themselves to be trapped within the system they operate: managing vast tracts of monoculture by the use of harmful pesticides. These practices compromise ecological processes and biodiversity, and in turn future productivity, Henriksson Malinga warns.

High population densities in the smallholder areas in combination with poverty, insufficient soil and water resources management, and low food production increase the pressure on the communal lands, degrading lands and depleting the common resources. Henriksson Malinga and her colleagues likens the poor, low-producing smallholder famers’ situation to that of being stuck in a poverty trap. Any attempt to change this situation must go beyond offering subsidies or credits which in the past have proven to be insufficient and have even exacerbated the poverty.

Conversation between a researcher and a commercial farmer.

Changes are needed, but they will be difficult

To escape the poverty trap, a combination of land reform, financial support and increased skills on how to develop sustainable, multifunctional agriculture is needed. When it comes to land reform and giving smallholder farmers better access to agricultural land, there are significant hurdles in the way. South Africa has over the past two decades struggled to pursue sustainable and equitable land reform to amend the historical injustices. Also within the smallholder communities, there are both formal and informal agreements and kinship networks that cause unequal access to land and natural resources among community members.

All these factors make change difficult. However, failing to even consider them risk cementing current inequities and the unsustainable management of the land.

“Embedded in the landscape are vast inequities originating from historical discrimination laws, and, because of their lack of access to land and natural, financial and technical resources, smallholder communities risk remaining trapped in poverty,” Henriksson Malinga warns.

Methodology

The researchers developed a mixed-method approach to assess the varying nature of several different ecosystem services, as there exists no single comprehensive method that captures the wide range of services associated with agricultural landscapes. They combined in situ biophysical and social data, using participatory mapping, in-depth interviews, and expert assessment to quantify the supply and demand of ecosystem services in cropland and grazing land. This approach enabled assessment of the social-ecological coproduction of ecosystem services, as well as the diversity of values attached to the services.

The set of ecosystem services selected was carefully chosen based on the following three criteria: (1) relevance to both smallholder and commercial farmers (2) representation of different service categories to help capture the multiple goals and dimensions of a multifunctional landscape and (3) feasibility of collecting primary in situ data or availability of secondary data from the study area.

Link to publication

Request publication

Henriksson Malinga, R., G. P. W. Jewitt, R. Lindborg, E. Andersson, and L. J. Gordon. 2018. On the other side of the ditch: exploring contrasting ecosystem service coproduction between smallholder and commercial agriculture. Ecology and Society 23(4):9.

https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10380-230409