A new study identifies the key role of coalition-building and information lobbying during the reform of the EU Common Fisheries Policy. The results were surprising in that pro-environmental interest groups were successfully able to push for sustainability reforms. Photo: Ocean2012, click on image to access source

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Fisheries Policy and reform

Tactics, timing and tenacity

How pro-environmental interest groups were able to push for reforms of the EU Common Fisheries Policy

• The 2013 European Union (EU) Common Fisheries Policy reform was surprising in that it resulted in a major shift of the fisheries policy towards sustainability

• The inclusion of the EU Parliament as a co-decision maker in the Common Fisheries Policy reform marked an important change in the lobbying landscape

• The benefits of newly-formed coalitions and the tactics environmental interest groups employed gave them influence necessary to effect significant changes

When you’re confronted by an immovable object, you have two choices: concede defeat or become an unstoppable force. This is exactly the challenge facing people working within sustainability issues. Their choice is clear: succeed by becoming an unstoppable force. But to succeed, understanding the ways in which policy reform can be achieved is critical. That still remains a black box for many.

Insight into how reforms occur is exactly what Kirill Orach and fellow centre researchers provide in their recent article in Environmental Science and Policy. The article looks at the recent case study of the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) reform, which was initiated in 2009 and completed in 2013.

The results of the 2013 EU CFP reform were surprising in that the pro-environmental interest groups were unusually successful in lobbying for specific policy reforms. We wanted to understand how they did it.

Kiril Orach, lead author

Quick and well-coordinated

Using interviews with experts involved in the 2013 EU CFP reform, the authors learned that changes to the decision making structure played an important role in the reform outcome. The key change involved the inclusion of the EU Parliament as a co-decision maker following the Lisbon Treaty of 2009. Prior to this, the final outcomes of the reform were decided in the EU Council, which has typically been pro-industry in its decisions.

With the reform now open to public scrutiny, and with intense public pressure being brought to bear on the decision makers in the EU Parliament, the stage was set for a well-coordinated information campaign to succeed.

Pro-environment interest groups were both quicker to shift their lobbying resources to the EU Parliament, as well as forming coalitions to consolidate the message and key proposals that they brought to the reform. By contrast, the industry interest groups used tactics that had been successful in previous reforms, and did not focus their resources on the EU Parliament to the same degree.

Orach explains: "Between 2009 and 2013, increased public awareness of the plight of fisheries and the pressure this placed on the EU Parliament decision makers made them particularly receptive to the information provided by the pro-environment interest groups."

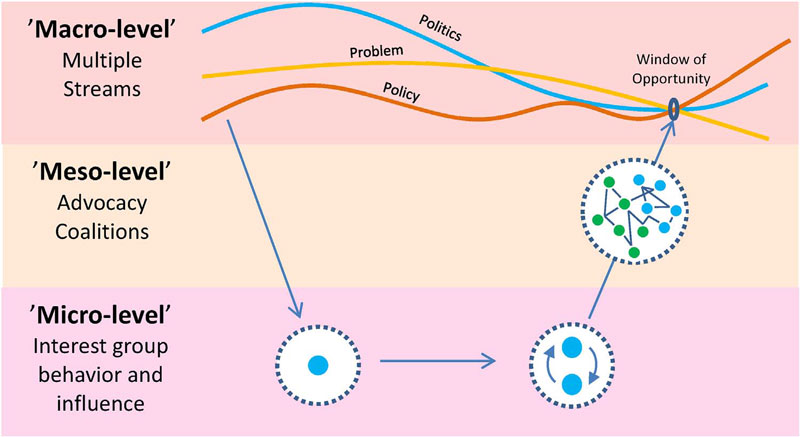

Synthesis of theoretical frameworks used to conceptualize interest group influence on the dynamics of the policy process. Click on illustration to access article

Coalition is key

The formation of coalitions by the pro-environment interest groups was cited as a key contributor to the impact that they were able to have on the outcomes of the reform. In coalition, the interest groups were able to share information with each other and with decision makers, spend time on public campaigning, and increase both their capacity and legitimacy of representation.

The public’s response to awareness campaigns was then also able to change the perceptions of the challenges facing fisheries and bring about consensus on the need for change.

As one of the interviewed experts explained: "I think there was an acknowledgement […] that we had really hit rock bottom in terms of the stocks we knew about. There was a consensus that things cannot continue as they are. […] Even the Council had a starting point of "yes, this is going wrong.""

The long history of public awareness campaigns on the plight of fisheries was also critical for when the ‘window of opportunity’ arose in the 2013 EU CFP reform process.

Further studies

The work of Orach and colleagues has shown how interest groups are able to force major changes in policy, despite governance system inertia and institutional obstacles. In the future they hope to focus on additional aspects of lobbying such as information flows during policy reform, and they hope to test various lobbying scenarios using agent-based modelling.

“Given the state of the natural environment and the need for sustainable policies to protect it, this work will be valuable for understanding how we can adapt to achieve them,” Orach and his colleagues conclude.

Methodology

To trace the activities of interest groups (IGs), the authors interviewed experts who were involved with the reform process in various capacities. Experts involved in the reform process, representatives from important IGs, as well as from the EU Parliament and the EU Commission, were interviewed in person, or via telephone/Skype. Interviews lasted between 30-40 minutes for decision makers, or 60-90 minutes for experts or IGs.

To assess the effect of IGs lobbying efforts the authors coded the policy position of each IG relating to four key issues: stock management, multi-annual plans, a discard ban, and quota access rules. These four critical issues considered during the CFP reform were identified from position papers, media statements and other documents produced by the EU Commission or IGs. After coding the issue ‘scores’ for each IG, the authors used preference attainment analysis to determine which IGs were favoured by the final policy decision outcomes.

Link to publication

Orach, K., Schlüter, M., and Österblom, H. 2017. Tracing a pathway to success: How competing interest groups influenced the 2013 EU Common Fisheries Policy reform. Environmental Science and Policy. (Published online: 05 July 2017).

Kirill Orach is a PhD candidate doing research on the role of interest groups in the relationship between policy and social-ecological change.

Maja Schlüter’s research focusses on analysing and explaining the co-evolutionary dynamics of social-ecological system with the aim to develop Social-Ecological Systems theory

Henrik Österblom's research focuses on globalization and marine social-ecological systems, in particular how fisheries and marine ecosystems are managed. He is also deputy science director at the Stockholm Resilience Centre