In a review published in Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, researchers discuss how active citizens may meet and partner up with local authorities. They propose a more inclusive, “mosaic” style governance to connect a variety of citizen networks. Photo: K. Krejci, Brooks Park, San Francisco (CC BY 2.0, click on image to access source)

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Active citizenship

Small tesserae in a grand mosaic

Mosaic governance: introducing approach that can better account for various actors engaged in urban green development

• Active citizens can improve resilience of urban green infrastructure

• However, uneven capacity and capability to take the role of an active citizen can yield selective participation and favour certain interest groups

• Active citizenship come with a diversity of benefits as well as challenges, both which could be helped by the support from a mosaic governance approach

Some people have just had it with waiting. In times of increasing urbanization and pressure on green spaces in cities, some citizens are taking a more active role in managing and protecting the urban green.

In a review published in Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, centre researcher Erik Andersson and colleagues discuss how active citizens may meet and partner up with local authorities.

By looking at examples from the literature as well as cases from three European cities, the authors believe citizen initiatives could take a more prominent role in a more inclusive, “mosaic” style governance. This means open up for and connecting a variety of citizen networks dedicated to the development of urban areas and finding ways for local authorities to support them.

“One of the main factors to successful partnerships is the context-sensitive participation of local authorities who could help deal with some of the challenges active citizens face,” Erik Andersson says.

Link to publication

Request publication

DIY resilience

Andersson and his colleagues believe that this mosaic governance approach can be seen as part of a “Do-It-Yourself democracy”, a more nimble governance approach less dependent on government initiatives.

However, active citizenship comes with a few challenges. It relies on voluntary participation, which means commitment may vary or be short term. Funding can be highly insecure and the accountability among the participants can be unclear.

Mosaic governance acknowledges relations and interdependencies not only between ecological and social scales, but also between the geographically distinct urban landscapes, community identities, and specific practices of active citizen groups across the city

Erik Andersson, co-author

The issue of ownership, responsibilities and level of engagement can be solved, Andersson argues. Partnerships can be flexible and solutions need to fit the local needs.

“An actor need not have the same role in all partnerships, and being open to assuming different roles in diverse partnerships is important for inclusive governance,” he says.

Success stories

The authors present three examples where citizen initiatives have successfully contributed to improved urban planning. In Amsterdam, Netherlands, members of De Ruige Hof Nature Association have managed 13 hectares of derelict land for over 30 years. Today, the area boasts a rich biodiversity including several red-listed species and several ecosystem services contributing to ecological resilience, such as increased pollination and reduced CO2-emissions.

In Malmö, Sweden, citizens have responded to the challenge of urban expansion by launching urban agriculture projects that focused on supporting local community employment. The projects adopted a polycentric governance approach where several actors from different parts and layers of the city where involved.

In Edinburgh, UK, a community group called Granton Community Gardeners have operated ten gardens on local authority land for six years without government input. The group provides healthy and nutritious food, education, and an alternative to food banks for the most vulnerable. It also engages citizens from a wide range of ethnic and economic backgrounds to participate and exchange knowledge in farm-to-table projects.

Hard work needed

Andersson and his colleagues believe governance needs to involve a diversity of actors across multiple levels of decision-making. This means an approach that is sensitive and attuned to the many different actors involved. It also means hard work: it is unlikely that any one single partnership configuration will lead to perfect results for both the environment and local people. There is limited research on impacts of already existing approaches; experiences and insights that can point to the different benefits and forms of collaboration is very much needed to convince authorities and public bodies about the benefits of mosaic governance.

”Mosaic governance acknowledges relations and interdependencies not only between ecological and social scales, but also between the geographically distinct urban landscapes, community identities, and specific practices of active citizen groups across the city,” Andersson concludes.

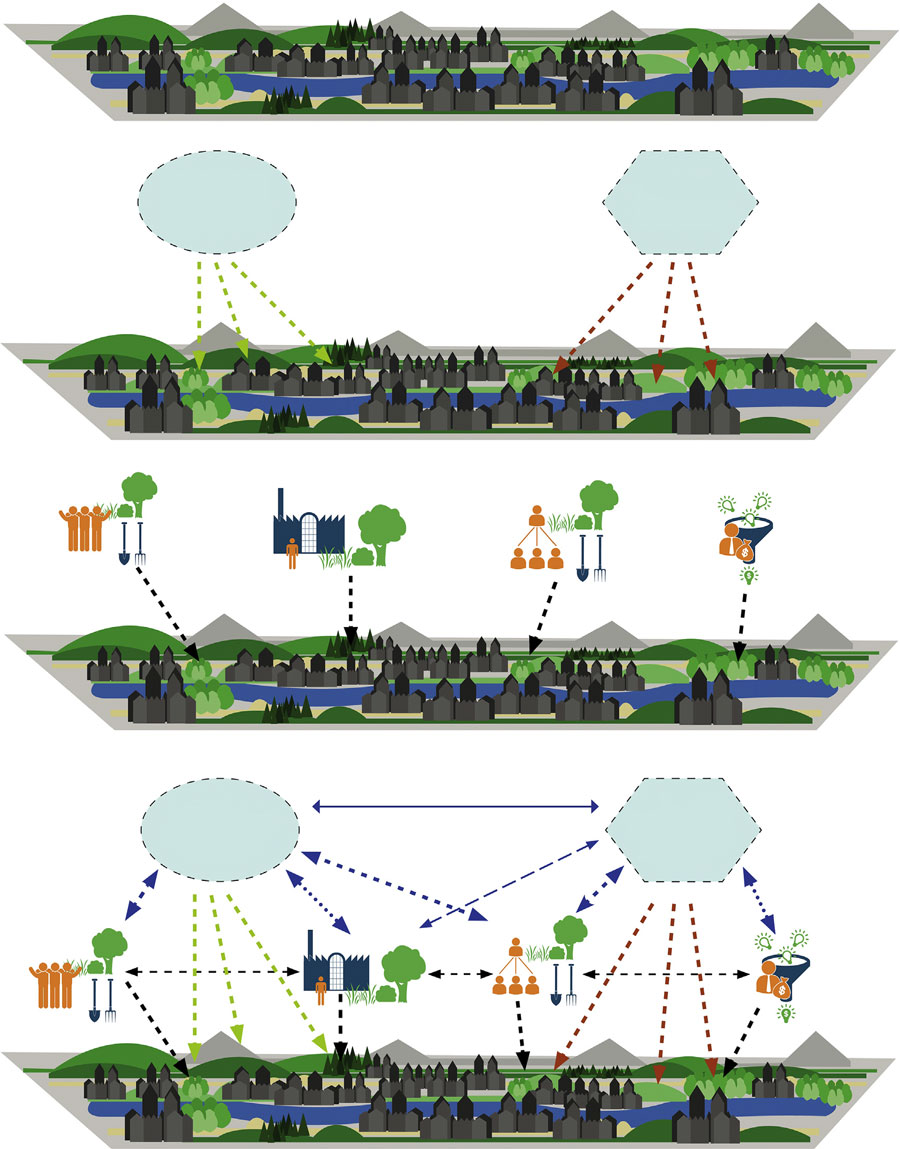

a) Urban green infrastructure: urban green spaces are diverse but ecologically interdependent, often represented as a mosaic landscape.(b) Traditional municipal-led planning and management to enhance and maintain urban green infrastructure. (c) Independent contributions fromactive citizen groups to enhance and maintain local green spaces. (d) The challenge of developing mosaic governance to enhance horizontal andvertical integration of policy and active citizenship (in order) to enhance urban green infrastructure. The diversity in blue lines between municipalsectors and active citizens signifies the diversity in this relationship, dependent on, for example needs and demands from different types of citizengroups related to the institutional diversity of how citizens self-organise.

Buijs, A.E. Mattijssen, T. J.M., Van der Jagt, A.P.N., Ambrose-Oji, B. et.al. 2017. Active citizenship for urban green infrastructure: fostering the diversity and dynamics of citizen contributions through mosaic governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2017, 22:1-6 DOI 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.002

Erik Andersson’s research focus on multifunctional landscapes, and he is one of the leaders for the global food systems and multifunctional landscapes/seascapes research theme