In a study recently published in Frontiers in Psycholgy, researchers tested whether an information campaign designed guided by insights from psychology and behavioural economics could help promote recycling of food waste. The campaign led to an increase in collected food waste of more than 10 kilos. Photo: Ö. Holmstad/Wikimedia Commons

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Pro-environmental behavior

Nudging the neighbourhood

Insights from psychology and behavioural economics can help households improve their food waste habits

- A new study used community-based social marketing and nudging approaches to spark pro-environmental behaviour among residents in a city district in southern Stockholm

- An information leaflet which explained the benefits of separating food waste from normal garbage was designed, urging residents to “join your neighbours to recycle your food waste!”

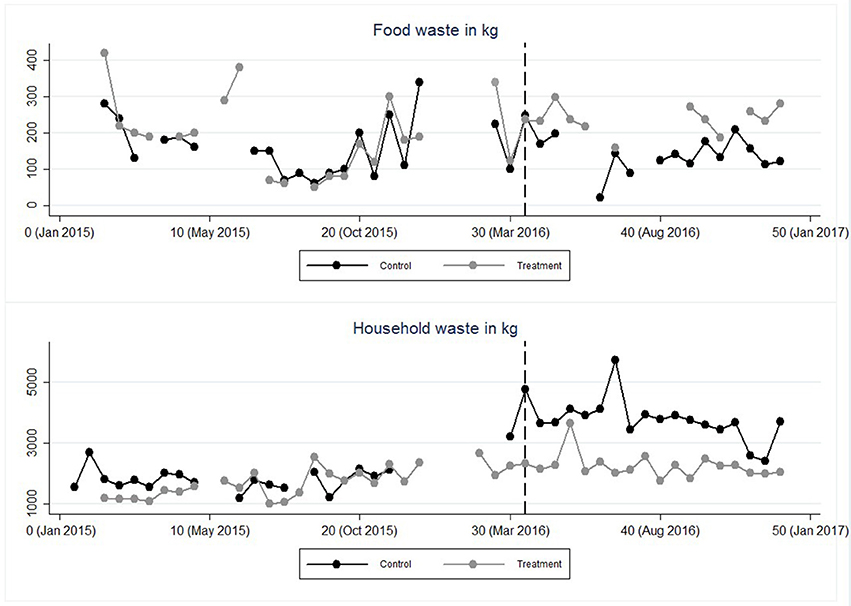

- The amount of food waste recycled increased from approximately 19 to 32 kg (on average per sorting station) among the residents that were part of the treatment group compared to a control group

With calls for large-scale social transformations and staying within planetary boundaries it is easy to forget that change usually starts with ourselves. Most of the environmental problems we face today are rooted in human behaviour and even seemingly small efforts such as recycling and reducing food waste can have large, positive impacts on the global resource use when aggregated.

Out of all the food produced in the world approximately one third is lost or wasted. It also stand for 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, consume a quarter of all water used by agriculture and generate more than $900 billion in economic losses globally every year. That is why promoting pro-environmental behaviour among consumers and urban inhabitants in particular needs to be a priority. Unfortunately we often struggle to make the change happen.

Just providing information is seldom enough. The question is: how can things be done better?

Nudging and social marketing

In a study recently published in Frontiers in Psycholgy, former centre Master’s student Noah Linder together with centre researcher Therese Lindahl (also Beijer Instittue of Ecological Economics) and Sara Borgström from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, tested whether an information campaign designed guided by insights from psychology and behavioural economics could help promote recycling of food waste.

“Information campaigns are often used in efforts to promote pro-environmental behaviour changes, but unfortunately they are seldom evaluated, at least not with a solid experimental design. Even rarer is analyzing objective outcome measures and long-term evaluations,” lead author Noah Linder says. As a result there is currently precious little knowledge about how these interventions influence behaviour, and how the effect may change over time. “This study shed some light on these knowledge gaps,” he argues.

The study used community-based social marketing (CBSM) stemming from social and environmental psychology and nudging (behavioral economics) approaches. The experiment took place in Hökarängen, a city district in southern Stockholm.

CBSM aim to make psychological insights available for practitioners and build on traditional commercial marketing techniques in order to create more effective social campaigns where the aim is to benefit communities for the greater social good. Nudging is subtle efforts to promote or change a certain behaviour in a predictable way. It is not allowed to prohibit or remove any choice alternatives and it must respect people’s free will. An example of a nudge is introducing smaller plate sizes in buffet lunch restaurants to decrease food waste. The customer still has the freedom of all-you-can-eat but the smaller plate size makes it so that fewer people end up serving themselves more than they can eat.

In an effort to nudge a whole community, the researchers tapped into the force of social norms to spur change.

Visible effect

They designed an information leaflet which explained the benefits of separating food waste from normal garbage. The leaflet, a three-page print with text and a few pictures accompanied by two recycling bags, used descriptive norms, urging residents to “join your neighbours, recycle your food waste!” rather than messages that focuses on saving the environment or the more financially focused “save money by recycling food waste”.

The researchers also included phrases that the residents could relate to in a tangible way: “If all households in Hökarängen would sort their food waste it would be enough biofuel to support 15 garbage trucks for a year.”

To test the efficiency of the leaflet, a total of 474 households where targeted, with 264 households in the treatment group and 210 households in the control group. The leaflet was sent out to all apartments in the treatment group in April 2016 and measurements in how much food waste was collected took place over the following eight months.

Before the intervention the average amount of collected food waste in the treatment group was approximately 19 kg more per station (9 in total) than the control group while after the intervention it increased to almost 32 kg. The effect of the intervention was still visible and statistically significant eight month after it was sent out.

Data points indicate aggregated data on food and household waste registered for all stations in the treatment and control group respectively. Each point represents waste collected over the 2-week period described above starting from February 2015 to December 2016. Note that some of the variation is due to different number of collections in each period. Click on illustration to access journal article.

Valuable insights

The researchers believe the information leaflet helped increase the recycling of food waste in the area and that much can be learned from their study. Insights from this study can also be used to guide development of similar pro-environmental behaviour interventions for other urban areas in Sweden and abroad, thus improving chances of reaching environmental policy goals.

Noah Linder believe there should be more cross-referencing between CBSM and nudging. Despite an increasing amount of research on how to promote pro-environmental behaviour scarce attention has been paid to connecting these two frameworks.

“CBSM generally has a more holistic view on behaviour change and present guidelines in line with the ones used in this study. Nudging on the other hand, can help expand the toolbox for changing behaviour. We recommend CBSM researchers to look into this more,” he says. Similarly, users of nudging can learn a thing or two about social marketing approaches from CBSM.

Methodology

The researchers designed a leaflet which was sent out 474 households. A Difference in difference analysis was then used to evaluate the effects of the intervention. The data set include data on food and household waste gathered from nine sorting stations in the research area from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2016. The waste was weighed and reported by the waste collection vehicles during each collection. Food waste was collected and reported in kilos every second week totalling 373 collections for the entire period. The study was done in collaboration with the housing company Stockholmshem, Stockholm’s largest housing company and owner of the majority of apartments in Hökarängen.

Link to publication

Request publication

Linder, N., Lindahl, T., Borgström, S. 2018. Using Behavioural Insights to Promote Food Waste Recycling in Urban Households—Evidence From a Longitudinal Field Experiment. Front. Psychol., Vol. 9. DOI: doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00352

Therese Lindahl’s research broadly focuses on human behavior as it relates to the environment. This implies that she is interested in the individual and collective behavior of natural resource users facing different forms of social- ecological conditions.