A new study looks at the complex networks in small-scale fisheries trade and why all actors involved in getting fish to market are not always accounted for in trade analyses. Photo: J. Lokrantz/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Small-scale fisheries

Untangling the net of small-scale fisheries trade

Study looks at relationships within small-scale fishery market systems, moving beyond economics transactions and fisher-trader connections

- New study looks at complexities of small-scale fishery market structures in Zanzibar, Tanzania

- Study highlights importance of understanding the fisher-trader relationship with respect to the broader societal-system in which it’s embedded and considers gender roles

- Study also points out that more needs to be understood, such as which actors are more negatively impacted by market or fishery development interventions

There is an old rhyme, “To market, to market to buy a penny bun. Home again, home again, market is done.” The rhyme points out the buyer, and indirectly the trader or seller, but leaves to the imagination the baker, distributer, deliverer, and a number of other important players in getting that penny bun to market.

In small-scale fishery (SSF) literature, not all actors receive the same attention either. The focus tends to be on the fisherman and his activities, masking other actors that also rely on SSF for their livelihoods and wellbeing.

Liz Drury O’Neill, a centre PhD candidate, and researcher Beatrice Crona, address this knowledge gap in a recently published paper in Marine Policy. It aims to understand the complex networks in SSF seafood trade; more specifically, why all actors involved in getting fish to market are not always accounted for in seafood trade analyses.

Masking some players or the depth of their connections in the game of seafood trade paints an incomplete picture of what SSF market dynamics are like.

We address the overarching issue of how seafood trade contributes to livelihoods and human wellbeing by asking; what does the seafood market system and its linked trading network look like? Who is involved and how are actors connected within this network? How do actors benefit from involvement in this fishery system?

Liz Drury O'Neill, lead author

The seafood market of Unguja Island

Drury O’Neill and Crona use a case of SSF trade on Unguja Island in Zanzibar, Tanzania and analyze the market structure, as well as actors and the relations among them. More specifically they use value chain analysis, a tool used to describe how materials go from entering the market to the buyer. In doing so, they identify three topics insufficiently examined in SSF literature:

1. Going beyond the fisher-trader relations

Crona highlights that, “examining simply one relational type denies the researcher a comprehensive understanding of what might influence the SSF market dynamics.” Their study highlights the importance of understanding their relationships, and that fisher-trader relationships, while often cited as more beneficial for the trader, are quite complex.

Social pressures from communities often influence their relationships. For instance, fishers would rather stick to a trade deal that maintains social harmony, rather than end their deal and sell to somebody else, where the outcome may be more economically advantageous for themselves. But by moving past just fishers exposed that traders felt even more inclinded than fishers, for similar reasons, to continue deals with their own customers.

2. Gender in fisheries

Like many other places, women in Zanzibar face cultural and economic barriers in the SSF market place. There, women tend to run more home-based business for local communities, and majority tend to be excluded from the higher-value market and tourism industry.

Drury O’Neill emphasizes that “this study shows the grave potential for many value chain actors, especially female traders, to be vastly overlooked in such development scenarios.” If studies just focus on the fisher-trader relationship or fishing activities themselves, development and poverty alleviation interventions risk missing an important group of actors.

3. Periphery actors in a complex fishery system

Finally, this study shows how a number of actors in SSF market chains tend to be underrepresented in the literature. One example is of those who assist with small jobs, such as preparing products for the market are often undocumented, yet are part of the value chain functioning and can rely on it for livelihood or food security.

While Drury O’Neill points out that a single case study limits them from suggesting specific interventions, she does suggest that to “address sustainable fisheries for all involved will need to account for the hitherto largely unexplored informal exchange networks in which fish trade is embedded.”

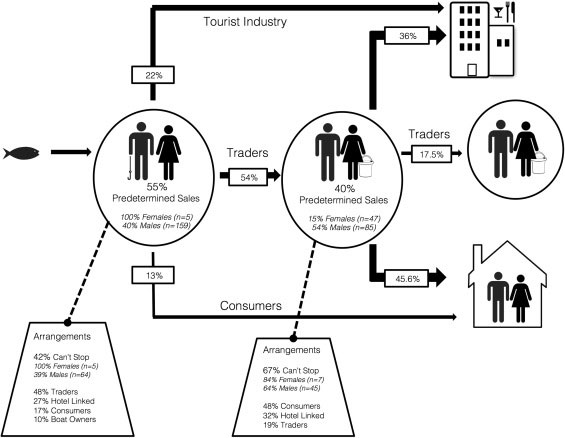

The main predetermined arrangements in the Small Scale Fisheries in Unguja, 55% of fishers define their sales are predetermined (circled in left of figure), 40% of trader respondents saw their own sales as pre-arranged (middle circle in figure). The arrows show to whom (and the proportion of respondents) the fishers or traders are dealing with in their pre-arranged sales. Consumers (home consumption) on the bottom right, traders right middle and hotels/restaurants and/or hotel traders top right. Only the most frequent sales paths are presented here. Reference: Drury O'Neill, E., and B. Crona. 2017. Assistance networks in seafood trade–A means to assess benefit distribution in small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 78: 196-205.

Beyond the coasts of Zanzibar

Looking beyond the coasts of Zanzibar, this study provides a complex overview of how local SSF market structures interplay with individual’s livelihoods, wellbeing, and food security options. As Crona notes, “These results provide a comprehensive picture of how seafood trade can allow actors access not just to employment but also capital, food, and favours flowing through personal connections held within the marketplace.”

While their study makes headway on understanding the complexities of SSF trade markets, it also points out that there is much more to be understood. For instance, why and how women can reap the same benefits as men when it comes to fishery development initiatives, or what type of market systems are more vulnerable to shocks.

With that beings said, the study provides a good basis for moving forward. As Drury O’Neill concludes, “This account of the Zanzibari system could serve as an important base for shifting future fishery development and governance discussions as it emphasizes the inappropriateness of management strategies that consider these fisheries as isolated from non-financial social relations (e.g. assistance), sectors and resources. Without recognizing this connectivity, especially in relation to poverty alleviation, then simple fishery or market interventions are likely to fail.”

Methodology

This case study, based on Unguja Island in Zanzibar, Tanzania, is the labour of five months of fieldwork conducted throughout 2014 and 2015. Drury O’Neill and colleagues conducted semi-structured interviews, participant and general observations, and also surveys among fishers and traders to understand the trade structure. A total of 306 surveys were administered to 168 fishers. However, as a result of both societal pressures and there being less women fishers as a whole, only five women were interviewed. As for traders, 138 surveys were conducted (49 women and 89 men).

All data was coded and analyzed in Microsoft Excel. Interview participants, or “actors” were also categorized according to a number of factors, such as fishing styles, gender, and location. Drury O’Neill and Crona focus on two fishery types for this study: small reef fish and octopus, two of the most important species groups for both local and tourist-linked trade.

This data was then used to understand fisher-trader links, and exchanges from different perspectives. A value chain analysis was conducted, to reveal a more thorough understanding of a small-scale fishery markets.

Drury O'Neill, E., and B. Crona. 2017. Assistance networks in seafood trade–A means to assess benefit distribution in small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 78: 196-205.

Liz Drury O’Neill is a PhD student, whose work focuses on the interactions between seafood trade, marine resources and small-scale fishery actors

Beatrice Crona, associate professor, works with topics in oceans and fisheries governance, as well as understanding different emerging global connectivities and their effects on social-ecological outcomes at multiple scales